Lilyillo, born in 1981 in Sydney, is a Canberra-based artist whose practice of making, seamlessly integrates the physical and digital realms. Deeply personal, her artistry is rooted in her childhood. Growing up with a carpenter father and parents who both cherished craftsmanship and art, Lily was immersed in a world where hand-made creations and the transfer of knowledge through things, held profound significance. These values have shaped her perspective, art, and ever-present desire to press against the mental and physical boundaries, of her self.

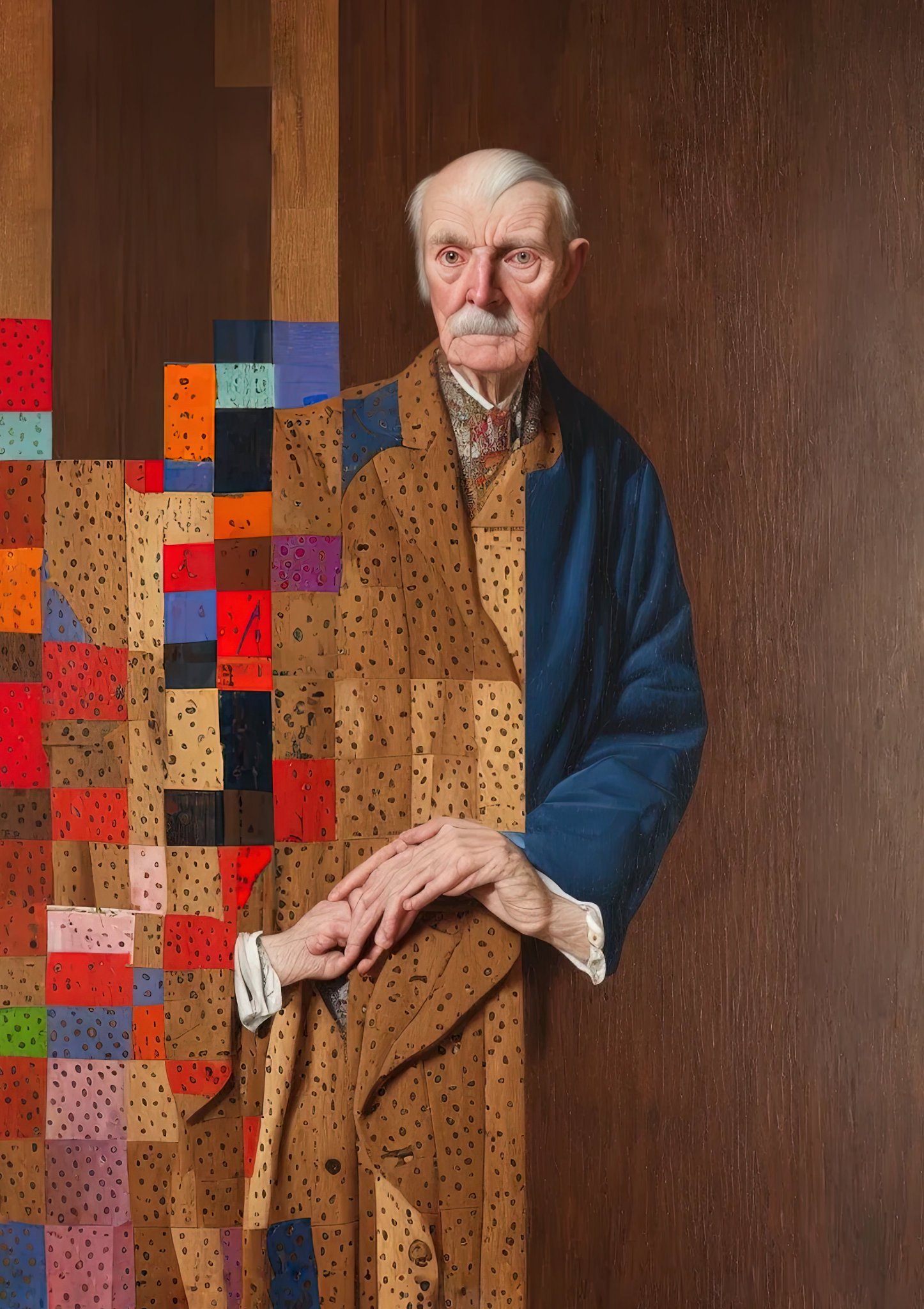

Lily’s artwork, rooted in her unique system, exudes whimsy and fervor. While many artists today use AI as a mere tool, Lily engages with it as an entity in itself. Her collaborative approach with AI is unparalleled, resulting in paintings that exude an aura of stillness, and depth. It was her exceptional AI-infused portraits that piqued my curiosity about her and her work, in the summer of 2022. By the end of that season, Lily’s portraiture had so clearly evolved even more than it had during the first half of 2022, transcending serendipity to emerge as a distinctive language in art—a language that, as of summer 2023, remains peerless.

Lily’s relationship with AI is, also, rare. Her introspective and contemplative nature has enabled her to foster a bond with AI that transcends traditional creative collaborations. Often, her works exhibit intricate fractal patterns blending color, wood, and whimsical geometries—a depiction of her own curiosities, as interpreted by AI. In our heart-to-heart conversation, from spring of 2023, she even mused on whether an AI, might actually be painting her. So our discussion allowed for a deeper reflection on the evolving role of AI, not just as a tool, but as a creative partner. This interview is a testament to that evolution.

JB:

It’s always good to start by focusing on the beginning. Of one’s life, but also the beginning of one’s formative years. And in this case, with you; it means your childhood and your days as a student. And the incredibly influential aspects of your father, and his woodworking. So to start at your beginning: where does your interest in portraiture, come from?

LI:

I’ve always been interested in portraiture, as its own subject matter, although that’s not always been what I’ve created, within my own practice. As a child, I was always drawing. And part of my work was focused on figures. I did a lot of life drawing growing up and I was interested in getting good at that; getting an understanding of anatomy and an understanding of the body and how to draw that with evident balance. Getting a sense of that. Not so much the face; except, when growing up I was around a lot of art. And my dad would take me to the Art Gallery of New South Wales and we would visit many exhibitions. So I was definitely taking in a lot of… art shows. And I think portraiture is such a compelling subject matter, because of the gaze and because we can see ourselves in the humanity of the subject.

It’s also a way for us to understand who we are and maybe—I think—that’s definitely something that I’ve been trying to wrestle with. That is: who I am; why am I trying to bring myself out onto the page or onto the canvas. So in some way, I try to be able to show that.

In other ways, I think all artists are doing that in some capacity. I’m always sort of wrestling with that… that concept of self. It’s not about representing the self; a self-portrait or something like that. That’s not what I mean. But more so elements of who I am and bringing that; bringing that to the viewer, I suppose. So even my portraits of male subjects, are actually in some ways self-portraits, and that I really resonate with. A lot. I’m trying to tap into emotions and a sense of intimacy and those deeper, more melancholic feelings. Emotions give us humans pause and provide us with something to reflect on. In life. Whether they are about ourselves or not. We all can reflect on those things, and they’re all aspects of us. I really do feel like, at this moment, I’m exploring the notion of self.

JB:

I was really struck by that actually; the way that you had worded that in our prior communications. When you were saying it was a difficult thing: finding it difficult to write about the self. I don’t hear many people like talk about it that way. It shows a certain amount of awareness, but it’s also just an interesting way to put it. Everybody thinks about the conception of their self differently, of course. Everyone definitely has more than just one version of their self; selves. So then how does one, be all; how does one be our best self at all times around the people that we care about, but also everybody else? The way that you talked about self, I just wanted to say, in the written word, was very interesting. I do think your portraits have a certain stillness to them. When I was, deeply thinking about your work over the past few months in preparation; I thought to myself: there’s a very dignified noble stance to them.

And there is a real sense of quietness; a very soothing calmness, to them.

LI:

And a reservation. They’re not full of huge emotion, or necessarily a rich deep happiness, but at the same time—it’s like you said—a sense of stillness. But I think that, you know, that’s just maybe how I am.

I’m quite a reserved person. And I’m alone a lot. My husband, myself and my children; we live in Canberra. We moved away 10 years ago from most of our family, who live elsewhere. And when we moved here, it was really isolating. I was a mother of young babies and I was all alone and my husband and I just… we kind of had to form a really good team. As I’m alone a lot, I have a lot of time to think, and make.

These are my people.

I am quite often alone. I don’t mind that. And I work for myself and I work at home, alone. I guess I’m caught quite often in my head.

JB:

Well, then I think we’re two in the same. I’m also an introvert with a small circle of friends, even as I live in Amsterdam. I love nothing more than to be alone with my thoughts, or with my library.

LI:

People who work in the Australian government are sometimes quite temporary and they move a lot. They’re not always going to live here, in Canberra, forever. And then you’ve got this other half of Canberra who have grown up here and lived here their whole life and they’re very, you know, patriotic towards Canberra and being a Canberran. Somehow my husband and I are neither of those things, yet of those two things. I really found, and find, it hard to fit in here. I think as well that living here draws a certain type of person, to Canberra; somebody who’s very security-focused and very privacy-focused.

So it can hard to build connections, I think, in this city.

JB:

I can imagine it’s a bit like The Hague here. Here in Amsterdam, I’m very choosy with my friends, because it’s such a transitory city. But you have all kinds of people who just move here for a year or two and don’t learn any Dutch. I mean, I’m as Dutch as they come at this point, as well. The Netherlands is a fascinating place.

It’s nice to learn how you got focused, in life and in your work, and how your orientation in the mind, also relates to your literal location.

Out of curiosity, because I know that you are also—alongside your work in AI—quite involved in the physical world, let’s say; to make it more basic, with drawing… So, one: are you also drawing portraits or just drawing in general? And two, my next question from that would be: do you only work in portraiture? Or do you only plan to work in portraiture in AI? Or at least, let’s say, concerning your minted work.

LI:

Do you mean the drawings that I do physically, on paper?

JB:

Yes.

LI:

I do watercolor and drawing, in a broader sense of the term. My master’s thesis, explored, I guess, the concepts of claiming knowledge through a subject. Diving into a subject and trying to understand a subject through tracing them mapping things. I suppose. That was my study; my practice. So I was making a lot of drawings, but it was more so mark-making, pin pricking through paper, and… mark-making on graph paper. Just repetitive mark-making. Which sounds quite banal and it actually probably is quite boring.

It’s something tied to that time in my life; not being really 100% sure as to who I was and what I wanted to say. And whether or not what I had to say was important. I spent a lot of my time as a student second-guessing myself. So my drawing practice was very different from portraiture in that sense. Although there have been moments where I’ve drawn a portrait and my husband has gone: ‘You’re so good at, you know, drawing realistic, naturalistic portraits.’ And for me, I always questioned why. Anyone can get really good at drawing a subject in a realistic way. And bringing that to the page. But I always wondered why; what am I doing with that subject? What am I doing? Just proving to somebody that I’m very good at drawing a figure? What is the point of all that? And I think this line of thought actually tracks through all of my work. Me, constantly wanting to be sure of why; why I have a need to create, and what the purpose of that all is.

But I now have come to realize that that’s actually its own process of overthinking, probably, and that maybe today, now I just, with a bit of age… having raised children and coming to art at this moment in my life… I’m less concerned, with the why.

I think I’m happier just to celebrate the subject; celebrate who I am through the subject; and to put something and actually someone, beautiful into the world. And that’s enough. But I think for so long, I was trying to figure out why. I do realize now: I don’t need a ‘why’.

JB:

That’s the great thing about art. For instance: I know all the ins and outs of academic art history, and I know the contemporary art scene, too. But the best thing I think I’ve found about art in general, in my own life, is that it can be universal and, or, personal.

There’s always a choice on the part of an artist between realism and abstraction.

Can you talk about how you utilize, or view, abstraction?

LI:

When I was young, I did a lot of figure drawing from life. I badgered my parents to send me to life drawing class when I was 13. Before that, my dad was a big influence. He was really always… teaching us perspective and how to draw things, realistically. I think that was a value of his, because he is an architect, and he understood space and how perspective works and how we would draw, say, a table with legs or a street that, you know, goes off into the horizon line and things.

JB:

Very nice.

LI:

He would teach us that as young children. And yet, we were brought up around abstraction and he painted in oils too. My dad also made paintings and we had them on the walls, but nothing about them was portraiture-based. But I was very keen to learn how to draw the figure. And so I did ask to go and do this life drawing class, because I was interested in being an artist from a very young age, I suppose.

So I wanted to hone that aspect of the craft.

My mom had enrolled me in an art class, which was, I think, learning how to draw or something like that. I don’t know. Something pretty basic; and I did go along, to the first session. But it was tiresome. Learning how to draw some round balls and tone them… That did not interest me at all. Humans, figures; people and emotions. These are the early things that fascinated me. Anyway, I came home and I said: ‘No, I need to do life drawing. Not draw apples and balls.’ So I did drawing classes for about eight years. And I really did learn how to draw there. Life drawing is mostly a sort of learning by doing. You’re often in a class where you’re just constantly, every 20 seconds, redrawing and redrawing the figure. So you learn just by sheer volume. It is the practice and the passing of time, tracing and redoing and rethinking and reworking that I’m interested in experiencing. And I think I have always had a sort of understanding of balance and line and form. So I, yeah, I just sort of took to it. And I’ve never stopped.

When I was 17, 18, I went to many art classes in high school and we had some projects to do, and I drew some portraits. But then, I went straight into university. I think I was probably grappling with why… why create? What is my voice; what do I want to say? And I didn’t really know, like I mentioned. So I chose to do a Bachelor of Art History and Theory, rather than a BFA, because I really wanted to understand my place in art history and what’s come before me. And then: how do I fit into that narrative historically? I think I just needed time to figure it out. So I didn’t make any work for a few years, because I was—yeah… I was sort of stuck, I suppose.

But then I was drawing, in a much more abstract way after that. I wasn’t doing a lot of figurative work. And I think that, as I said, abstraction became a useful way of occupying my time with the act of making. At least when I really wasn’t sure what I wanted to make. Although, I was making. But I still can’t; I can’t shake that.

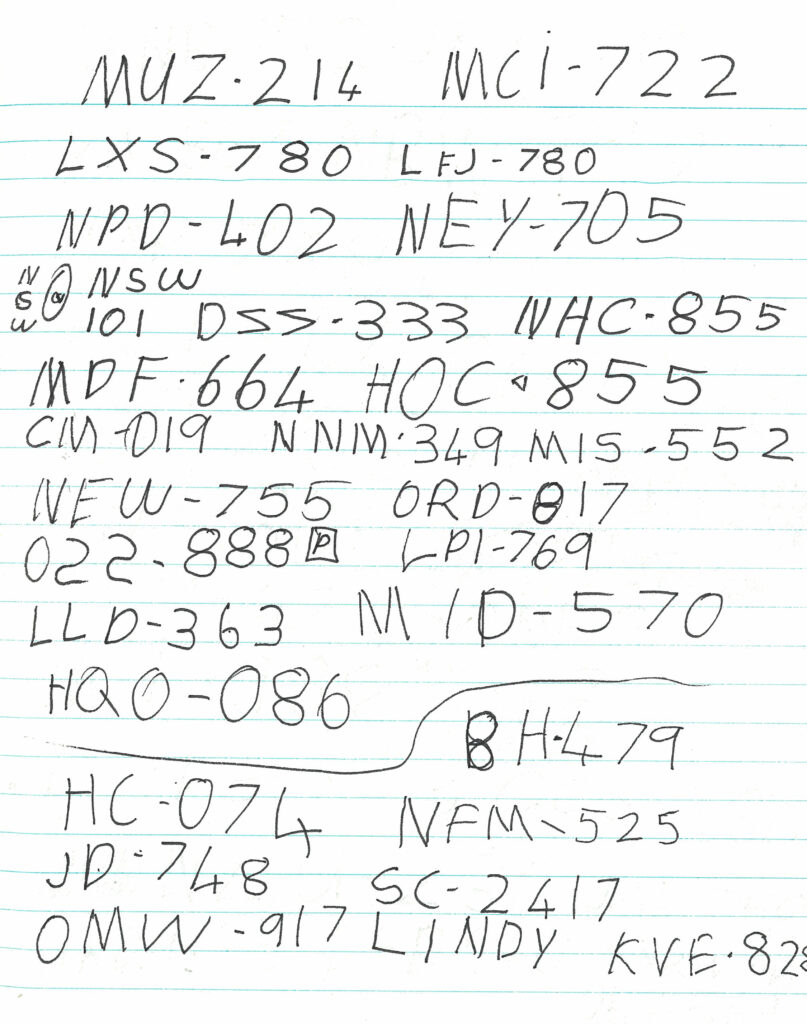

When I was a child, I used to carry a little notebook of only blank lines, at all times. I would fill it with running writing, because I could see my mum writing, and filling up space, in her notebooks. And I thought, ‘She must have so much purpose, so many important things to put on that page.’

And at some point, I realized that I wanted to have purpose. I wanted to ‘fill up pages’, too.

JB:

How interesting.

LI:

I wanted to have that. So I also had a little notebook, and I filled it with writing, which was gobbledygook; you know, it meant nothing. But I filled up space with this running writing that was mine. And then I gave myself that purpose and said: ‘Okay, when we go in the car, you’ll bring the notebook and you’ll write down all the number plates that zip past the car, and you’ll record those number plates in your book.’

It was also very odd, and kind of police-like, really.

A kind of record-keeping, in some ways. It was a thoughtless exercise because it’s not like I had to put myself on those pages. It was just an activity of filling space, claiming my space. And I returned to that in my early 20s. Trying to figure myself out. Again. What do I have to say? And in the meantime, I will claim my ground, until I’ve figured out what that actually is.

Abstraction to me is something like that. It is really valuable, for me, in biding time.

JB:

That makes sense. I do think your work, most of your artworks on Tezos, for instance; I would call them abstract, but not in a Rothko abstract sense.

Lily:

Mmm.

JB:

I think it’s the abstraction of the backgrounds. Simply stated.

LI:

There’s a sort of surrealism coming through. That’s for sure.

JB:

Which brings me to my next question. I understand your father had, like, an obsession with wood, and woodwork. Could you talk about your… your engagement with woodwork, in your work? And how you use it? The backgrounds of so many of your portraits are full of wood; all kinds and types, and its so unique. How did you come to it; because it’s obviously a development in your work.

What does it allow you to explore? That’s, I think, a good way to formulate this…

LI:

You know what? Woodwork, for me; it’s always been something I’ve loved.

A sense of craftsmanship with carpentry that I was always around growing up. I love those memories. It wasn’t something that was taught to me, carpentry, that is. Though woodworking in my family; it’s very much passed down the male line in my family. My brother—I have a twin brother; he was taught the craft, and these tools. My dad’s father and his grandfather and his great grandfather: all carpenters.

So these tools have been passed down generation to generation, in my family. And there’s something… I’m quite a nostalgic person and there is something very beautiful about old things like that, which have carried a history with them. As a child I was drawn to wood patterning, and woodwork, and well-crafted woodwork, and all that. When I was growing up, we had a workshop in one of the rooms in our house, because my dad was always building something, in our house. And so we were just around all these tools and so making was just part of what we did. I think it was something that I… I definitely yearned to learn those woodwork tools—and there is something gendered here, I think. So it just wasn’t passed down.

My dad is getting older. He just turned 80 and I suppose in the last few years I’ve been talking a lot with him and finding out about… his life, his childhood. His dad died when he was 12. And so he took on… he really took on the role of being a carpenter very young, with his dad’s tools. He had to go and become an apprentice carpenter, and then an apprentice architect. You know, hearing about his life lately; it has been very connecting for me. And we weren’t… necessarily always connected like in that way.

So it’s been very bonding.

When I started, you know, working with AI in itself, I was really thinking through the role of the tool; the artist’s tool. Because AI, obviously, is a tool that we all can use; but at one time, sort of last year, in March or April; there was a lot of unkind criticism of AI, as a tool. And AI in general, being used by artists. And that’s even from a ‘traditional’ artist’s perspective. There were lots of people who were very anti-AI and there still are. But maybe it’s waned a little bit. So I suppose I was very conscious of, sort of: ‘Okay, well if I come to this tool, as a researcher, I want to understand rather than criticize something that I don’t know how it works and what it can achieve. So instead, I’m going to use this tool and see what I can get out of it.

I asked myself: ‘Can I use AI to find a voice? Or will it just be a generic AI aesthetic?’

That was definitely something that we saw last year.

JB:

Totally.

LI:

So for me, in permeating this new space; I was not interested in that, per se. But I came to it with a researcher’s mind, sort of wondering, ‘Okay, well, can I, you know, find a voice here?’ But simultaneously, I was really aware of criticism from traditional artists, having, you know, come myself from a traditional background, too. How did I feel about that? How do I feel about that?

In the end, I ended up drawing parallels from that experience, to the experiences I explained of generational craftsmanship in my family. Obviously, the whole process reminded me of my father and his tools, and the very physical making that I grew up around. But also physical painting, sewing, patch-working… A whole range of different crafts that were all a really big part of my life, growing up. And so I was really taken with trying to figure out, at least in my mind, ‘How can I bring those elements to AI and see; see what happens?’ That’s been fascinating.

And it’s been wonderful. I mean, AI, is a really a magical process. And somehow all this converging of ideas can happen in an instant. So yeah—there is something, you know, that I can’t look away from.

JB:

That’s well said. One thing I want to ask you about as well, beyond, let’s say, the role of AI itself in your work… as in, the larger picture. When it comes to the actual work, your work; what I think is incredibly interesting about it, is that it’s developed its own language, alongside the wood of the backgrounds; and that is very much rooted in fractal patterning. Anyone can throw up a wood panel background behind a portrait; but yours are so… of you. For instance: does that come from something such as your crafting and dealing with fabrics as a child? Or is it now, its own aesthetic that you found your way to, and merged with? When we first got in touch, in 2022, I wrote to you that in some ways your work—at the time—was a bit Cubist, in that sense. I don’t think it’s on purpose, but I’m curious about the ideas behind…

Your thinking around that.

LI:

For sure. It’s a bit of both, I think. I mean, it is built into my prompting, in the sense that I talk about different fabrics and patchwork as one of the many prompts I would use, a lot of, in a lot of my work. But initially, I think when I was working with different AI models, when I came towards that aesthetic; it was within and built into the AI model itself.

JB:

Okay… Can you explain that a bit more?

LI:

I’ve seen other artists come to something similar. I can see that that is somehow built into the tool and I’m happy to find that in a way, as it’s a true collaboration then, isn’t it? Me and AI. You’ve got yourself that you bring—you are also the tool; but the tool also can have its voice.

There’s something really beautiful, about that, when working with AI.

I’ve, you know, also worked with patchwork in my watercolor practice.

But, they are specifically patchwork blankets that I was painting, in a very geometric way. So I’m drawing from a range of different media aesthetics that I know already, and bringing them to AI tools, as well. I used to patchwork with fabric when I was young. I wanted either to be an artist or a farmer and my idea of a farmer would be like, you know, an Amish farmer. That means, to me, no technology and churning my own butter and that kind of real return to something very simple, and quiet. And so I think when I was young, I was also; I was sewing a lot and making quilts and making things with fabric a lot, because that’s actually how I could… how I could make things. My own things.

JB:

Makes sense.

LI:

Yeah.

JB:

That’s also why I think it’s really interesting to talk you, as an artist, for instance, just as an aside. Because, your work is so personal, and I think that that also makes it so intriguing. It’s not just pretty images made using AI. It’s so clearly original work, and there’s so clearly a personal stance within it, and… I’m personally not interested in the secrets of what people do with AI, or how they get their AI results. That doesn’t interest me from a journalism perspective. More so, in your thoughts behind those thoughts… the thoughts behind the thoughts, which become infused with your prompts.

LI:

Hmm.

JB:

And I think you’re interesting as well to speak with, because you also have a traditional, physical—raw art background. As in, an academic background alongside your AI work. So you approach it from a different angle. Since it’s all thinking work, quite literally, I think it really all goes into the process. So it’s very nice to hear, your views. The other thing that was really interesting to me beyond like the fractal patternings and the wood and just, seeing your work all develop over time, is seeing that sometimes the fractal is like… the body or the clothing. Or sometimes it’s even the background itself. I think it’s just really a multi-layered sort of like, charrette, of different ways to create, and a way to come to the results you’re arriving at. At least your work that’s minted. Especially your portrayal of hands and bodies; limbs.

And I know maybe part of that’s part AI and part of it’s you. Maybe you can even push it in the way you want to. But, um… I think it’s really… it’s really well suited to your work, because it has that contrast with the really hard angles of the patternings from textiles, or woodwork.

Your elongation of limbs is fascinating. Almost mannerist.

Can you talk about how you approach that: exaggeration?

LI:

I mean, when I started with AI, there was definitely these anomalies that happened. And I’ve got to say, that more and more people are coming around to the idea that these are beautiful things. But I was struck by them straight away, early last year. And that, to me, was… an aspect of the beauty of this new tool, and working in this way, that it has… it has its own way of learning and it’s trying to understand how to imagine these things; fingers and hands, and limbs. There is a sort of contortion that happens and it’s, like you said, definitely something that I… It’s not that I try and amplify it, but it’s not something that I steer away from at all. For me, there’s enjoyment in these anomalies.

It’s a kind of true collaboration with the tool, if you can embrace those things. And I have; it’s funny, you know, we were talking about my husband saying, you know, why don’t you just draw beautiful, realistic things? Obviously, AI is getting to that point where there is just perfection and people are able to get that from the tool. And I come back to why, again, this question of: ‘What is the point?’ And where is, you know, what I’m trying to say with it? For me, I’m here to almost amplify AI and care for it, and show it off; what it’s imagining. And that, to me, is… I revere it. It’s important. It’s a part of the outcome of the work, is that it’s not just me. It’s also the tool. Maybe it’s a finite moment in time where we can get those results and I… I… I want to just kind of love that, about it. So yeah, I think it’s like you said: I’m trying to amplify these moments to some extent in the ways that I’m prompting. Though quite often, I don’t have to do too much, to do that. I mean, AI is just at a particular moment. Maybe it will be lost eventually. I’m not sure.

JB:

In your work, there is definitely a contrast between the fluidity of the elongations, the fingers and limbs, with the hard fractals really creating… not only a tension, which makes it visually interesting. But what’s mesmerizing about your work, is that that same underlying tension, is not literally visible. But then there’s also this overall sense of calmness. Stillness. Which, engages the viewer.

LI:

Thanks.

JB:

Could you talk about your master’s project? I understand it’s very special to you, and that some of its ideas, you still use in your work.

LI:

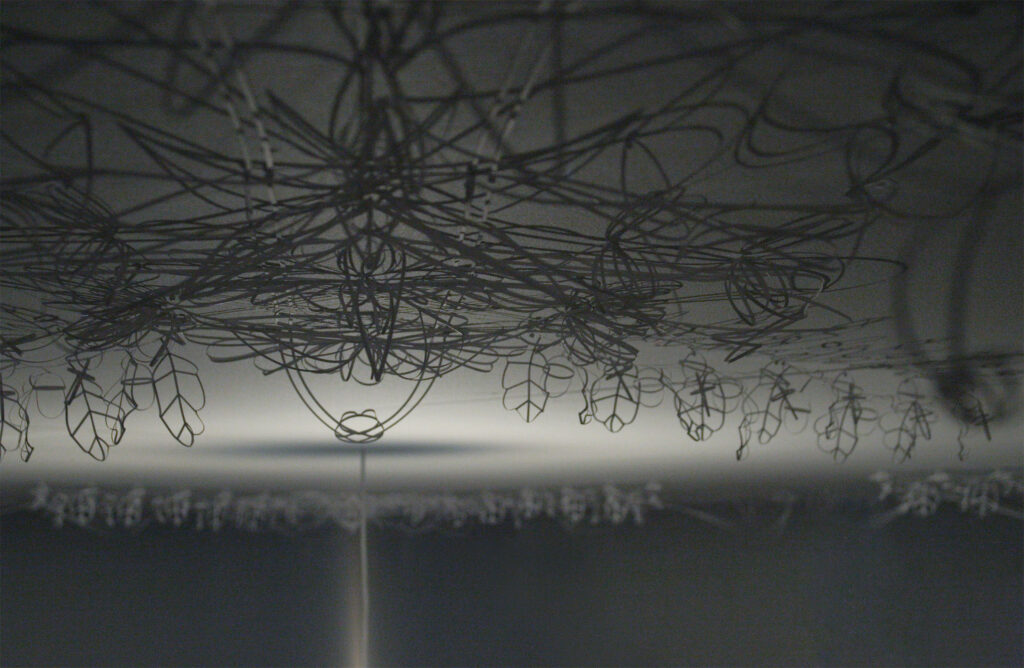

During my masters I was, like I said, sort of claiming… claiming my ground; claiming knowledge. And I think that’s what I’ve tried to do a bit in my practice Is it… are you here referring to the ceiling project?

JB:

Yes…

LI:

I can talk about one project that I did, which was a recording of the ceiling in my childhood bedroom. Which I think does tie into my current practice in a couple of ways, but just inhabiting intimate domestic spaces is something that I think through it, a lot. I think through memories of my childhood home, and I sort of spent a lot of time, like introverts do, inside my… mind. So I wanted to create a drawing of the ceiling that was in my childhood bedroom, which I had a memory of. It was sort of an exercise in memory. But also an exercise in tracing the pattern, because it was a very patterned federation ceiling, which had acorns, oak leaves, and some ribbons.

It had these things built into the plaster work of the ceiling.

JB:

That’s special.

LI:

Obviously, I’m dealing with a concept of destruction and making…

Destruction and making, destruction and making. Because of that struggle and battle between the traditional artist and this new tool. But a part of that is, you know, looking back at my dad building our childhood home. He was a carpenter with his tools and his skill and his sense of craftsmanship, he was a Freemason, so he was also very much entrenched in the concept of working with one’s hands and what we, can create with our hands. And then he was building and renovating this house for us. Then at nighttime, he would wake up and hear tiny termites eating the house and eating through the wood…

In the end, the house was; it was long gone. Probably before he even started building rooms and things. So the house had to be destroyed and then we moved to another house. But this is part of my memory process and reclaiming that home, but also exploring that concept of loss and destruction of something that we created. It’s central to me.

JB:

That’s both sad, and beautiful.

LI:

Then we moved to a new house, and after we were there for about six months, there was this massive storm in Sydney that came through, one night; a huge hail storm. And I was probably eight or something; nine. And the hail… it broke all the roof tiles on the house and we ran with every container we had into the house to block and catch water that was coming through the ceiling. Horrible.

In some ways, I love these things that happened to us all, because they become poetic when we grow older. They are something we can draw from, and look back on. But for my parents, it was very devastating. The house was flooded and the roof had to be replaced. The ceilings retained this liquid, this water, and grew mold. It’s humid in Sydney.

Incredibly humid, in summer.

So the ceilings grew mold, like black mold, all across them. And by this point, I think my dad was… utterly burnt out. He had just lost the house he had built to termites, and then we’d moved to a house that he was going to renovate and build out for our family. And then this storm. He went into a depression, I’m sure. He, you know, he sort of lost all his energy and drive to make anything happen. We stayed in that house for another 14 years and it was a really stagnant space, as in, literally.

And so the mold grew. And grew.

My father was also stagnant in his career, and my mum and his marriage; their relationship suffered. It was a tricky, stagnant time. And so we had these black ceilings in our house, for about 14 years—which is poetic, I think.

JB:

Definitely.

LI:

So anyway; I remember tracing this ceiling, lying in bed at night time and, you know; the mold had sat on the flat surface of the ceiling. There were… protrusions of patterning that came in the ceiling plaster that was less moldy, I suppose. I used to look up at it, a lot. So my master’s was me recalling the ceiling and drawing it. So I built a ceiling in a gallery where I exhibited that piece and the ceiling. I built a floating ceiling down from the rafters. And I taught myself how to do that and I got all the tools and made the ceiling. I was so proud of myself, because I was born to a carpentry-architect-fellow and I wanted to somehow prove to myself: I could do this too. Then I drew with thin tiny strips of paper, that ceiling pattern. And I pinned it up onto the ceiling as a drawing. And so that was my big project. But drawing, as I’d say, lace; and then the light in the room caught that paper and created these shadows, and sort of memories of that ceiling, kind of cast onto the walls and things. So, yes, that’s it.

JB:

How beautiful.

LI:

I want to circle back to AI here, and an experience I encountered when I was creating a portrait, first in Stable Diffusion, coming to prompt; a written prompt. And getting outputs. One of the outputs I would select and use to input into DALL·E, and from that, I’m using in-painting and out-painting to expand the frame and position my own subjects.

That’s part of the process.

And whilst using DALL·E on a subject—a female portrait—I started to out-paint from her central figure and build out the frame. And as I did that, she was in a room with white walls. And as I moved around and out painted, with more sort of basic prompts, just saying a wooden floor and a cream wall around her… AI, the DALL·E platform, placed these wooden, like two-by-four planks on the ground, near her feet.

And she sort of hovers in the space. And that’s when I realized, you know, AI was painting a self-portrait… of me. And I thought, in that moment… that was me, building my ceiling.

And I think there are moments like that when working with these tools that are undeniable and very mystical and wonderful. Another thing that constantly draws me back to using AI, the tool, is that there are these types of surprises and, also something life-giving about this process.

JB:

First of all, it’s nice to hear your take on how you kind of literally use your AI, as a toolbox. But more like spiritually and figuratively. Also nice, to now know how you see it and approach it. Because I don’t think everybody has that view, or let’s say, that not everybody that uses AI as an artist, approaches it that way.

And yours is so clearly… Super personal. The work you mentioned about your bedroom…

‘She stayed up late to build a ceiling’, is its title…

I mean, knowing what you’ve just told me and then knowing this work and also knowing its minted description, as well; it just makes it more… you can tell there’s just layers and layers and layers behind it.

…It’s not been my goal, in speaking with you, to try to place you in a tradition of portrait painters or anything. Your process is what’s always intrigued me.

LI:

Thanks, John. Can I also add something, too?

JB:

I was just going to say, is there anything else that you want to add?

LI:

I just wanted to also say that, when, when you first asked me to write my thoughts down on paper: I was quite hopeless at it. I’ve got to admit. But something that I haven’t spoken to you about and that I did write down, was more in relation to how I came to these tools and what I wanted to get out of them, initially. Because I have also always collected things, and one of those things is found photographs.

I was always collecting portraits of lost people, you know, discarded in antique stores and bookshops. Things like that. I was always drawn to these things as a child. We used to go to antique shops a lot. I think I don’t know whether it was just of that time, or if my parents just liked taking us there. But we would go through them, often, really. I was always drawn to finding little shoe boxes that were left under the counter or a box they would have of all these photos that accumulate, I suppose, at an antique store or thrift shop or something. I love that.

I’ve got, thousands and thousands of found photos. I previously did a series of work that was around the photographer of these type of old photos because I have a collection of found photos, wherein, in the frame of these types of photos, is the shadow of the photographer.

A shoe or a foot that stands, just in the frame.

JB:

Yeah…

LI:

You can tell that it’s a photographer, because sometimes they’re just like, holding a small box brownie camera; so they’re hunched over and a shadow is cast in, or on, something. There’s a trace element to these types of photographs.

JB:

Yes…

LI:

A trace of the photographer left behind. And I always liked that in some ways, because ‘the father’ held the object, held these cameras, which actually, now I’m saying it to you, circles back to the male lineage.

That’s quite often what happens: the father would take the photo of the children in the garden, or the family on holidays, or something like that. So you often get shadows of the photographer cast about in the image, in the photo. I was always so drawn to that element of the author; the gaze of the author upon the subject. I find it fascinating. But when I first came to AI, and AI photography—or post-photography or synthetic photography; whatever we’re calling it right now; it wasn’t a huge thing this time last year… AI then, was really grainy and Mid-Journey was giving really textural outputs, and AI photography had yet to kind of have, or make, itself known, in a big way, as it is now.

And I was really interested as to whether we could get photographic outputs from AI.

And what that would look like? Does AI understand the role of the photographer in creating these new photographs, or an ‘AI’ photograph? I tried prompting to get that shadow of the photographer cast into the AI, and extensively tried getting the trace of the author. But AI being the author; is that self-referential? Like; what is that? It was fascinating, you know, as a process, to get these shadows of photographers cast into the AI image with AI. Somehow referencing, its own self, through a prompt.

JB:

That’s really intriguing.

LI:

I thought it was an interesting starting point, in examining portraiture. And that brought me to the subject of AI portraiture as well. But yeah; I had thought it might be useful to you. I don’t know how it would work.

JB:

AI photography for areas where photography doesn’t, or didn’t, exist.

LI:

Exactly.

JB:

Well, I think it’s really, very, very fascinating that you’re… pushing AI intellectually, as well; not just based on output. As in, thinking: ‘Can we get the actual creator of, “quote”, the photograph to appear in front of the camera?’, is an interesting intellectual exercise in itself.

You could write a whole essay on that!

LI:

You absolutely could. I think it’s an interesting thing, within photography theory, when you bring and apply this idea, when working with AI. Susan Sontag writes about the memento mori; or, the photograph being, as she says, a record of death. Because that moment is gone; you can’t reclaim it. It records the literal death of a subject. And I think that’s a really interesting thing to contemplate when we now see AI. We are literally witnessing the birth of these new subjects through AI. And, you know, there’s this really beautiful aspect of it. We no longer have memento mori, we have memento vivere, or something else like it. And it’s beautiful. And I think there’s a lot that could be written about it, in that way. I’d love to read about that.

JB:

Totally. That’s one of those things that requires one to be really impassioned about the subject; and then, it just flows from inside of one’s mind, out into the world.

And impassioned, is certainly a way to describe your mind, and work.