The work of artist Maisie Broadhead (London, 1980) stands at the intersections of painting, sculpture, and photography, creating a unique dialogue between these disciplines. Born, raised, and still based in London, her career as an artist seemed to have been predestined, surrounded by a family deeply entrenched in artistic pursuits. Broadhead has honed her language through her interests, studies, and personal development, which has been significantly influenced by her education in Three-Dimensional Crafts at the University of Brighton and her subsequent MA in Jewelry & Metal, at the Royal College of Art, in 2009. Today, she leads her studio in London and imparts her knowledge and experience as an artist, teaching as an Associate Lecturer at the Royal College of Art.

Her approach is often informed as much by a reinterpretation of the Old Masters as by a conversation with them, incorporating elements of her life, family, and friends into her work. These relationships add depth and meaning, highlighting the collaborative nature of creativity. In this extensive interview, Broadhead delves into her artistic process, revealing the plethora of connections between her work and her personal life, and the importance of her family to that process. For her, the process itself is equally as important to the finished piece, no matter the form that the finished work arrives at. Nearly each of Maisie’s works is the result of an elaborately staged situation, with intricate self-constructed sets.

Broadhead’s artworks, particularly her pearl portrait series, transcend traditional boundaries, blurring the lines between painting, photography, and sculpture by merging 2D and 3D elements; such as frames that seem to warp and melt, and pearls adorning women, which emerge from the canvas, and puddle on the floor below. Her work is an exemplification of her skillful merging of form, idea, and execution—and her unique perspectives on the art, of art history itself. Combined with her personal history and family narratives, Broadhead had created a captivating body of work that challenges traditional art forms, and ideas. This unique blend of past and present, personal and universal, not only challenges traditional art forms but also invites viewers into a world where art is not just seen, but felt and experienced.

JB:

I’m most often really interested in painters, most of whom are dead. But it’s quite fun to talk with painters, and artists, who are alive.

MB:

You get something back in a different way, I suppose, if you can converse with people.

JB:

Absolutely.

MB:

Well, I’m very grateful to talk. It’s great to chat and I’m flattered that you’ve asked.

JB:

Which brings us to speaking now.

I have, for years, thought your work was so incredibly interesting. I had never seen anybody… I mean, it’s rare that people do anything with the Old Masters in any meaningful way beyond just, you know, collages and things like that. So to find somebody working with them full scale; not only at full scale, but—you know—producing them as physical artworks too, I knew something more was here; sculpture meets photography. To begin, where are you from in the UK and where are you based now? And how did you find your way to a life immersed in the arts?

MB:

I’m from London, London City. London. I’ve not gone that far. I am from the Hackney section of East London. I was brought up between East and North London, and now I’m somewhere in the middle and I’ve got a very large family. It’s quite hard to leave them, as you realize when you come from a big family; it’s quite hard going and living out in a world, or a different city where if you’re sort of used to them being in your lives all the time, even for good or bad, it’s very weird living in a place without them. So I’m from London and I’ve got four sisters.

I think London is home and does feel like home, but again, I think the most important thing is probably the rest of the gang being here. My family. So many people like living in cities now, which I fully understand. But I think London’s got this kind of hook, in lots of different ways. I’ve also lived in New York City when I was younger.

JB:

Have you lived anywhere else besides New York City and London?

MB:

I think London always felt like it was home. I’ve not sat down and said: I want this job, I want that plan, I want to be there or in this city or in that place. So it’s always just a bit of: I’m still here, I’m still doing it. So no, when I worked in New York I really was quite young and just very much enjoyed the nightlife. I’ve worked in bars, I waitressed, and played lots of pool.

JB:

Were you on the Lower East Side, it sounds like?

MB:

It was actually in the early-2000s that I lived there, in Brooklyn. I loved New York City, but I just got pulled back into London. I came back for Christmas and then got sucked back into it. I don’t remember any person in my family who’s moved anywhere outside of the local highway that surrounds the city. So, I don’t know how it goes elsewhere. I mean, in many ways, I feel quite lucky that my hometown was London, I’ll be honest. You know, like, it’s got lots going for it.

So, it’s not like I was from a very small place and then couldn’t move elsewhere.

I’m fortunate that London is home.

JB:

Can I ask you then; how did you then find your way to deciding to eventually, when you were younger, study jewelry?

MB:

I come from a very artistic family. My mum’s a textile designer. She was a jeweler back in the 1980s. She had a lot of connections with Amsterdam because that was a very big art jewelry scene there at the time. She was a bit of a pioneer in that rather small world back in the 1980s, and my dad’s a glass blower. My stepmother was a potter. So I think growing up in London with some very—like, all my parents’ friends, were artists—so you know; Thursday nights were always out at somebody’s opening. Not always looking at the artwork, but understanding that that community was what I wanted to be part of. I didn’t have to seek it out; I grew up around it. And later I just thought it was quite normal. I didn’t have to rebel. My parents always supported my desire to be an artist. I got only got A’s in art and photography. So in a way, it was almost by default, that I became an artist. I studied a making course down in Brighton when I left my A levels, which was a kind of course called ‘Wood, Metal, Plastic, and Ceramic’. It was a course about, I guess, physically making. You could just choose one of those subjects; you could specialize in one material. When you say to people that you studied jewelry, people assume that you set stones.

But I kind of understood it in this slightly different way; that it could be worn, but it could also just be a statement. It could just say something.

I was always engaged in that side of things.

I didn’t want to go and set up a practice or a jewelry brand or something. I think I wasn’t kind of sure why that was the way to do it. So, again, knowing that I was interested in art but had this ability to make things…

At 22, I ran off to New York City for a little bit. Thought I could somehow move away, again, and again, this precious life from my parents and the way everyone around me was quite professionally established and then not really quite knowing how to articulate my voice in materials. And I thought, after art school, I’d leave knowing what to do. And I definitely, definitely didn’t. I didn’t even know what my material was.

And I had given up photography, you know; I couldn’t really continue with the photography.

My uncle is not an artist but when I was 16 he gave me a projector and I stuck it in my family house, in the basement with the laundry machines. And I would set it up in the darkroom. That’s probably the first and only time I’d done something really creative with photography I think. But in that way, it felt very honest and I wanted to work out how it worked. It’s funny that I totally forgot about that moment, until I started going back into the idea of using photography as the end product in itself, as opposed to just as a means to document 3D works of art.

So again, I left college, and didn’t do very much. I kind of bounced around as you do in places. I worked in a jewelry shop. I used to work, selling all kinds of jewelry. And some of that was diamonds and gold, and some of it was, again, slightly really fun pieces.

I worked for a jeweler at that time, making all of his production work for him. He was a kind of a fashion jeweler. And that was fun; you got to see a different bit of the fashion world.

He always did collections for fashion shows and such. So we’d often go to Paris a few times a year and peddle the wares. They didn’t pay very well at all, but it was fun. I got to go to fashion shows and I would never have gone to them otherwise. The free tickets got me into such places; the experiences were entertaining and probably actually quite informative. And then I also had a job as a sort of picture researcher for a book about contemporary jewelry.

While working on a book as a researcher, I was meant to find the right pictures to illustrate what the essays and things said. I realized that I kind of knew more about this jewelry, than the book’s editor. There was a moment when I realized that… I think I’ve got the greater reach of knowing who’s making what in London, jewelry-wise. I ended up coping out of that, and I think that was probably a catalyst for me going: I should probably go back to school.

I studied for a jewelry course at the Royal College of Art, because there was a teacher; the guy running it then was named called Hans Stofer. I loved his work, he was fun and he was a jeweler; but he was also an object maker. And he had struggled with that sort of world, again, which we got to talk about before, and it’s kind of… jewelry not always being about something that you wear, and more about an idea, and a signal for something else.

I applied and got in to the full program. That was just a bit of a game-changer for me. So that was when I started making jewelry. None of it really worked for me. I had nothing that clicked. And then this tutor of mine… It comes down to a few people, you meet in life. He was one of those few, really important people for me, in my own development. Then I was invited to take part in a show by a man named Carl Clerkin. And he invited me into this big manor house. Sometimes in the UK we’ve got these kind of old, what would have been like, owned by the kind of very wealthy landowners, manner houses—that then get given over to county local authorities to work with. And they have exhibitions in them and stuff.

And he said to me, ‘I want you to take part in the show, in Pitzhanger Manor, here in London. I really like these pictures.’ I had taken these funny pictures where I dressed my family up as Victorians. And so I dressed them up as old people; people from my past. He said, ‘I really like what you’re doing with that. It’s the nicest thing about you, mate, is that it’s your family in your work.’ And he’s a big family guy. I thought: maybe I could do something that I thought had a bit more of a sense of humor to it, which I always thought was quite important. If I was enjoying myself, then the work would be better. Always.

So he said, ‘Come and do the show, I want you to be in it. The only premise of it is that it needs to be about: what does home mean to you?’ I was finding it really hard. And so I ended up looking at these paintings that were in the manor house; prints, actually, by Hogarth. And my partner is a massive Old Master painter lover. In a way it was him, who dragged me around, when I first met him, a long time ago, to see paintings. On one of our first trips abroad to Italy, he did the thing of: in Rome, he went and said, ‘You know, I’ve got to show you all these churches.’ And you go and you put in a pence, or you know, a euro or whatever it was at that time, and then you get Caravaggio on the wall and it lights up for a few minutes. I’ve been dragged around museums as a kid all my life and never really saw art in that way that he showed it to me. And he kind of changed my focus. I mean, you get so excited about it when someone is explaining these paintings to you. It was quite infectious really. And then when I started picking up the stories in these Old Master works, as well; it’s quite interesting.

But anyway, back to the show; Carl invited me there and said: ‘You know, do something you.’ And because I’d started looking at paintings and things in this slightly different way, and because there’s a reproduction of Hogwarth’s ‘A Rake’s Progress’ series on the wall in that manor house, I said, ‘Oh, what home needs to be is my family.’ It’s a big family. We’re all kind of in each other’s pockets, all the time. So I decided in this work, to just kind of stage it like a family portrait, which is like what you’d have at home. So they let me kind of… take the painting print out and put this replica one in it, which replaced ‘The Heir’, in the series. It’s called ‘She Pulled My Heir’, which is one of the first kinds of photographs I did that looked, at that stage, like an Old Master. It’s very dark and moody and Hogarth. And I also had the same number of people in my family as in the painting; so it worked out well, in that sense.

So I took this picture and I went back into college and my professor had said, ‘Amazing what you’re doing!’ But it wasn’t I remember saying, not my jewelry work; it’s not really my work. And he said, ‘That’s the best thing you’ve done since you’ve been here! Like, what are you doing?! You know, all the other stuff is crap compared to this!’ Something or other like that.

JB

So, this is how you wove your interests in the Old Masters into your work; the idea of home…

MB

What was interesting about this painting, Hogarth painting, is that it was from the Rakes Progress series. It talked about a sort of decline of a young man. So, it depicts a series of six scenes, and it depicts him inheriting loads of money. And in this first scene, he’s… he’s asking for his ring back, from Sarah. Obviously, before he knew he was rich, he was going to be marrying her. And in this scene, he’s sort of going; just give me back the ring. It is a bit funny: give me back the ring, and because I’m too good for you now. It’s this scene that’s quite important to understanding the story of the painting. And it’s quite symbolic that he’s indicated in this way, that when she’s giving the ring back, she’s in tears. And then that makes it even richer; the jewelry in this is the center of the painting’s narrative.

I’ll find lots of paintings that have got pieces of jewelry in them that have a kind of… Something that adds context to the painting or is an important feature of the painting. Often it’s very symbolic of something and I’d work with that idea, during my jewelry studies. I worked with these ideas so I could create images but I would also then make pieces of jewelry to go with them. So it was this kind of conversation, again, between different kinds of 2D and 3D works, which has always been a bit of a battle, and I was also very aware at that stage, for the first time, that people in my course were making things. But the only way people saw them was on a website, and therefore you needed to photograph this kind of work. Back then everybody went for the sort of straightforward pack shot, you know, on a plain background. And again, I realized I could make my final work, a picture. And that that could be the work itself. So, I realized then that I don’t actually need the piece in itself, anymore. So I dabbled, I did a series called ‘Jewelry Depicted’ and that was all whilst I was still in my study days.

JB

Could you talk a bit about how you came to use staged situations in your work? What do you hope that they convey, in a general sense; or better said, what was your intention when you initially began working in this way? Since so many of your works reference specific paintings or visual archetypes from paintings; do you intend to recreate them for the sole purpose of visual pleasure? And in what ways did you add your own narratives to them?

MB

To sort of go back to the idea of suddenly realizing that I liked the hook, or ‘in’, which the jewelry was providing in these works; but then I had to go back to this kind of honesty about: do I just want to put models in pictures and photograph it in this way? Is it really about the jewelry? And I suppose, probably through doing that project, I realized it isn’t. It’s more about the subjects in them and in most of my work, the people that are in the works, are my sisters or family members, or very close friends. So I realized that doing that with my family and doing these photo shoots where they all come round to the house for the weekend, and we eat, and they get dressed up and we laugh and have fun; it also started becoming part of the work itself. I treasure these kind of moments; these people mean something to me.

They’re actually, my people—and they’re intimately involved in the process of making.

When I graduated from the Royal College of Art I had five pictures on a wall with five pieces of jewelry, and that was my entire MA show. And immediately, at the show, the gallery I still work with now, Sarah Meyerscough came round and said, ‘Well, I’d like to show your work. But we just want the pictures.’ So I kind of went, um, okay. I remember her saying, ‘How much is it? And how many editions are there?’

I had no idea.

And so, as soon as I graduated, I sat down with them, and she signed me up for a year for a solo show. And I think it was the first time I realized that the photographs in themselves are the work.

I was always trying to work out this way of 2D, 3D objects; how do they sit together; how do they relate to each other? And realized that it could just be about the people and the narratives within the images. And I was lucky that my partner—who I was talking about—loved these paintings. He’s a director, a film director, and he has a very good understanding of how to light things. And so technically speaking, that’s how we started at the very basic level.

JB

Why have you zoomed-in on the Dutch Old Master painters as a key interest in your work?

MB

So to get to the Dutch Masters—which is from that series from my MA—was the first time I did this piece called ‘Which Way to Go’, which was the first one that I ever looked at this Vermeer as an inspiration. It was perfect for translating my process into an image, really. And many people have done this—recreate Vermeers—before. I’m thinking of Tom Hunter. He’s a British photographer who had done such a piece. And so it wasn’t a question of, ‘Let’s just utilize Jack’s skills, knowing that he could make something look quite beautiful.’ It was a translation of my process. The lighting is so soft, and we also used a bit of a smoke machine. And actually, they were both quite practical solutions to achieve the final result. So all of them were sets. We built sets, for those works. I still build sets today, too.

I had the making background, so the images were sort of constructed from, you know… I kicked my mum out of her studio, built the sets myself, and had all my friends help me. So again, it had a sociable sort of aspect to it. I didn’t pay them, but they got all food, and they all got a picture at the end of it. You know, that kind of thing.

And again, it was fun and I felt really alive when we did it.

So Sarah asked me to do another show, a series at five, and see what happens. And then my kids came along. So it was a very busy 10 years, and it just sort of all went by—rather quickly. And I sold just enough that I could do a new project. And that was always the goal: sell just enough to invest in the next one. I like the idea of taking things that we recognize, which is a reference to something historical. You’re sort of borrowing the gravitas that comes with that history in a little bit in a way. You recognize the value of the recognition.

JB

You’re making me think of the British painter who’s getting lots of praise as of 2021 or so; Flora Yukanovich, where she basically… It looks at first like a Fragonard painting, or like a Rothko painting, but when you get up close you see that it’s abstract. I think that’s sort of in the air right now; that it looks familiar visually or formally, but when you get up closer you’re like: wait a minute. I think that’s kind of what’s happening in visual culture at the moment, which is my own personal take. So it sounds like what you’re saying a bit, like the form is the value of the reference.

MB

Yeah, my work does come with that.

People know they feel comfortable looking at those kinds of things; works that reference old art. We all know that. So once you’ve then got that, you can then tell your own story inside of it. And for the sitters; my family were the ones I could be the most honest with when photographing. I like the making of the sets, and that’s wicked and fun—but I missed using my hands. And I guess because of my background in jewelry, I just love this conversation between the 2D and 3D.

JB

How did your studies in jewelry, affect the way that you use it in your work; I imagine that there’s a certain representational awareness on your part of how best to portray it within your work, knowing its intricacies. Your work is very intriguing in that in your portraiture series of ‘seventeenth-century’ women in pearls, the pearls that the women are wearing, literally break through the frame to become physical strands of pearls, which when installed as works in a gallery, fall to the floor in puddles below the framed portraits, or hang above…

Can you discuss the ideas behind the genesis of these works? Were there certain artists whose works and their aesthetics—such as Van Dyck and his fellow group of painters, like Adriaen Hanneman, most of whom were portrait painters active in England—influence you? Or did you feel free to borrow archetypal fashion motifs, from many?

MB

The works with pearls really came about from another show that I had with my gallery, a solo show. I started to ask myself: ‘What have I been thinking about? What’s going on in my world?’ And again, I went back to the fact that I’d been teaching and talking about jewelry so much, because I started teaching then, and at that stage realized that again; this beauty of the idea, that jewelry can signify something, without it having to be a diamond ring that people wear. So, I looked into this, I started researching a different kind of jewelry, in paintings, and I went—as I do I often—and spent quite a lot of time in museums here, and I studied the imagery and what’s being repeated, and it’s quite interesting that I gravitated toward works from the seventeenth century. Because pearls were so expensive at that time, they were more valuable than anything else. They had a difference, and they meant something different than what they do, now. And from what I understood, a lot of these portraits of young women were being painted with multiple strands of pearls at the time. These paintings were used, a bit like people would use their images, today, as profile pictures for the modern-day dating app Tinder.

For instance, these portraits were sent off as a way of, I guess it was, monarchies from Europe that were trying to sort of… Secure their position. And I didn’t know this until I started digging around in this history, that these paintings were sent around to different courts, to present these ladies to possible suitors. And so a young prince would have multiple paintings, and he almost chooses bride based on the paintings.

Which is bonkers.

And so then I was thinking, ‘Oh, this is quite interesting. Now you’re looking at these paintings—and aren’t they just about making the women beautiful.’ Then we’ve got things where we’re like: ‘Okay, well, maybe the more pearls you’ve got… maybe they are not actually about her. They’re less about the woman and more about their wealth. Just wealth. Or the illusion of wealth.’ And that’s been written about before. But really—how many can one get on without them being the joke? Your neck just falls over! How can a dress be purely made of pearls? How many can you actually embellish on the dress, without it going over the top? So, I think that, when I started this idea of thinking about pearls, in itself at that stage; I realized that they were a bit of a shackle for these young women. And don’t get me wrong, I’m assuming people will probably also think I’m a royalist, by the kind of work that I do. I’m not; I’m genuinely not.

The choices of things that get to go in museums; we have to have a conversation about what’s in them, you know, and how these works are selected for history. But if you’re talking about going into these museums, then a lot of the kind of asking the questions that need to be asked, you know, rather than just going, ‘Oh, these women are beautiful’; but instead, and equally, it’s important to understand what these works meant, at the time they were made. There was some darkness to those seventeenth-century portraits of rich women, and it’s not just about a pretty portrait. For those particular women, it had quite a lot of impact on their lives. Presumably they were being sent off relatively young, often girls, and then being used as currency.

And so the pearl—the actual pearls that emerge from my portraits in the pearl series—in a way were, a kind of representation of that, to me; that these women were currency for bigger things. The commodification of themselves, via the pearls. And so then I did these pearls that they were, you know, coming out of the frames and dropping to the floor, and attached to the walls and such. And I’ve event got one that’s called The Ball and Chain.

In Cockney rhyming slang it means one’s wife; a husband might call his wife, the old ball and chain, referencing prison. So in a way, I kind of like this idea that, instead of these pearls being a symbol of how wealthy these women are, it it was also going to be what brought them down, so to speak, in the end. It was, maybe, a little bit more truthful as to what was really going to happen to them, at that time.

JB

I love that.

MB

I love working with my framer.

Robert is his name and he is amazing; he’s this guy, that lives just a few miles away from me, and there are plenty of framers closer that I could try and work with; but I just… he’s the most wonderful character. You go into his studio, there’s sawdust everywhere, he’s always got a fag in his mouth. I mean, to the point where you’re like, one day I’m gonna come and his shop is gonna go up in flames. It’s just the biggest box of kindling ever. And he’s put these beautiful old frames in here, and he restores antique frames, you see. And he’ll often repair antique frames. So he understands that thing, of blending something in, making something look old, making something, restoring it back, even by making it new.

You’re giving it its value, by making it look old again.

The gallery actually put me in touch with him, and the moment I went down and visited him on the first day, I was like, ‘That’s it, this is kind of the relationship I need in my work!’ This is very important, too. I’d often sell work unframed before I met him, because I didn’t quite know how to frame it. And the moment I went and saw him, I was like, this is the added element that all these images need.

JB

Also with the kind of work you’re doing, I mean, you almost… the frame is almost, I would say, part of the work.

MB

It totally is. And again, Jack, my partner, springs into action when shoots are on and he’s incredible—wonderful and very supportive. But often it’s quite a solitary working experience. So to have Robert, who’s become a friend; his work is so good and he’s such a character, and for instance, sometimes all you want to do is just drop something off at his studio. But you get there and can’t leave; his work is wonderful; he’s got a very colorful history; and he’s fun to be around and discuss my work with.

He used to make all of Charles Saatchi’s frames back in the 1990s. So he helped me with the pearl series; I worked quite closely with him, trying to make sure that the way the pearls merged with the images, was just right. So I would bring up all of the prints, I’d print them, take them to him and then we’d work quite closely, and start working out the best illusion, possible.

I didn’t realize that element—the physicality of my work as he calls it; it wasn’t… it wasn’t… I didn’t realize, it was so integral until I started working on that project, and realized that that, was the work itself. My work really needed those frames to have that seventeenth-century feel, and it needed that element to bring it all together. I really, really enjoyed those pieces and they still… they are still selling today.

They’ve kind of lived on, a little bit.

JB

I’m particularly intrigued by your ‘Reframe’ series from 2018 at the Manchester Art Gallery—could you talk a bit about the literal frames of these works, which warp and are sinuous in one or more of their contours, thus breaking the idea of a traditional picture frame; much in the same way, but different from your pearl series?

MB

The last couple of years I’ve seen in numerous situations where people who had old collections of art, would often invite me to come and respond to them.

JB

Back in like 2016 and 2017, this was really the thing for museums to do. Commission an installation or exhibition that responded to the permanent collection, for instance…

MB

Yeah; there’s been a couple of places where that happened over those years. And in a way that’s the gift. You know where the piece is going. In a way it’s a bit of a design brief. You’ve been given this collection that you have to respond to, obviously artistically, but you need to, and you’re speaking to that specific collection. The Manchester Art Museum has a big collection of pre-Raphaelite paintings. I was really fascinated by them all… They had a whole bunch of them. So the British artist called Sonia Boyce, had done the residency exhibition at the museum just before myself. And so Sonia went in and she removed John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs from the gallery; that was her intervention. She wasn’t censoring it, but she was saying, ‘Let’s ask ourselves again, since we have these media and we have these collections, why we’re saying that these are the best works in our art history.’ And so it was being talked about in the country.

So it was all quite titillating that the women in these works were quite young and quite beautiful and naked. And there was a big understanding, that some of these artists used underage models back then.

And it caused such a stink here, her intervention. People were so upset about it. All of these kinds of slightly conservative people going, ‘Wait, did you take, you know, down this classic painting!? How dare she!’ But she didn’t take it away. No, she’s not taking it away. She’s asking you to kind of, I guess, question and be open-minded about its absence. They know that the artist—Waterhouse—had relationships with 15-year-old girls. Should we not talk about that? Yeah, we definitely should.

That’s not censorship.

It’s not trying to say that the painting itself doesn’t have merit or technical brilliance, but… when I visited the space, I kind of did a very simple thing. I went straight to the paintings and looked at them all, and suddenly had a bit of a flurry of activity in searching the Greek myths, and was like; ah! These are really good! There’s so much going on! And you can get lost in there with those pre-Raphaelites and all that stuff. And so realizing that the pre-Raphaelites had a very funny way of depicting these women as either sexy or seductive, as sort of seducers; so they were always very dangerous, or they were kind of, a bit pathetic. So it was either or. You know, women couldn’t be represented in art as something else, at that time. Sadly. When I started researching these works of this period, I realized the characters had quite a lot of different elements to their characters that weren’t always being shown, in these pre-Raphaelite paintings.

And so, I was also invited to come and respond to this collection of pre-Raphaelites at the Manchester Art Museum. The five pieces that I made were all in response to pieces that they owned in their collection. I tried to distort the framing of them. I liked the idea that perhaps the narratives that they were peddling; they’re kind of holding them and keeping them safely contained; but that also, they couldn’t be contained anymore. And it seemed that the frames had given up on just depicting them in, this way.

I like the idea that they’d given up, the women in the portraits, and that they were just sort of, you know, had these frames that are sort of conveniently holding them up in their poses.

JB

And did you also work with your framer, Robert, on those works too? Those frames are so unique and so special. Because the frames… that’s such an integral part of each of those works.

MB

Exactly. That’s what those pieces were about, really. I kind of went down the route of initially seeing whether I could sort of cast them myself, at first. But it turns out that’s really hard to do. I drew them all in pencil first. I was like, yeah, that’s gonna be cool. I was, pretty sure there was a way to make this. No problem, I thought! Honestly, the sweatiest six months of my life was knowing that the exhibition was coming up and that the frames were still in pieces. It was so much work, those frames, in a good way. That was very stressful. But I ended up getting a friend who’s an architecture student to help me. He helped me draw them, in the 3D modeling program Rhino. And so I ended up having to knock on an old mate who does furniture now, too, because he’s got a lot of CNC experience.

JB

You would need some of those skills in some way for those shapes. Whether it’s works that riff on the Old Masters, or work that is set in a series of ‘everyday’ situations, such as within a nondescript room of a house, such as a kitchen; all of your frames seem to be central to your work. Could you continue talking about your interests in frames, in the most abstract sense, in relation to your work?

MB

Yeah. So then what they did, was like we took—because they’re all too big for one piece of wood—and because they had a 2D and then a 3D element to them. Nothing could be printed, based on the initial Rhino drawings. So what I had to do, was in the actual Rhino drawings; I had to slice them up virtually and then lay them flat. To make like cross sections to kind of feed it through the machine. So they then ended up coming off the CNC machine as though you sliced it. And then I took them all down to Robert. And we had to jigsaw them all back together. So they were like an MDF; they were a Velcro mat or something, like kind of a composite material that we cut. And then they got sandwiched back together. And then he gessoed them in the old-fashioned way, so he uses like a rabbit skin glue and that.

Sometimes it’s amazing. But with these frames, I realized that no prints will print onto something that’s not flat. So I had to do all the mounting.

Again, it was all just a little bit mental; the quantity of work, which went into those works.

The frame itself was the project really. It was bringing this very technical, all kind of, again beyond my capabilities; to ask somebody to help me do that, to the point where I was asking somebody to help me cut things out on a CNC machine and then taking it all manually to get done in this very old-fashioned way. To put it all back together in the way a sort of traditional frame would be composed. So yeah, that was sort of what we’ve been doing since 2018. I think. That’s probably the last project I did where I worked directly with the collection.

JB

What I can say is that I was really intrigued by your work years ago, but also still. But I could tell there was something in the work, beyond the visual and the finished work that’s, let’s say exhibited, because the 2D and the 3D, as you say. I knew that I’ve worked with many photographers before, who stage situations and that’s the final work. And that was obviously very clear that was part of your work. But it was also intriguing to me that it was much more than that. And I could tell that it was more than that, but I wasn’t sure how. And I think you’ve done a really good job of explaining how you merge the 2D and 3D, in your entire process.

How do I say this? That situation around the work is almost as much of a part of the work as the final product of the work, itself. So bringing your family together; having dinners; building sets; all that energy is, of course, in the final picture. I wouldn’t say you’re a conceptual artist or a performance artist, but that, sort of sequence of acts around a work that leads to its final state; it sounds like that is as important to the work itself. It sounds like you really think about everything, super holistically.

MB

When you try and do something that you are particularly enjoying, and I know that from speaking to students, it’s very hard to get anybody else interested in it too, I think, if you’re not engaged in it yourself.

I suppose in a way that was probably the biggest lesson learned, certainly of studying art, kind of going: ‘We don’t enjoy it and no one else is going to enjoy it. Like, no one’s going to.’ Yeah. So yeah, they’re getting that sort of sense of like, again, being fun and having a fun element and a social element and a personal element is generally there and quite key.

JB

Well, that’s also why I thought your work was really interesting; because it’s about space in the most abstract sense, but for instance, it requires a certain level of thinking or abstractness in the most literal sense to be able to—like the peepers that you did, at the Brighton Pavilion—you have to have an awareness of that space. But if you’re just looking at that from a photography lens, you’re not really so aware of the scale that the pictures will be at and what the images will resonate with and the people in the actual space that are experiencing them so that’s why we’re getting back to this 2D and 3D. I could tell there was something more underneath all of your work that was pulling it together, beyond just physical elements that extend from a painting.

Could you talk about the scale of your work? Obviously, a photograph is a representation of a previous space or situation in time. What is the importance of realizing the manifestations of the works at a large scale? Is there a certain sense of detail or aspect of your compositions that are demanding of large scales?

MB

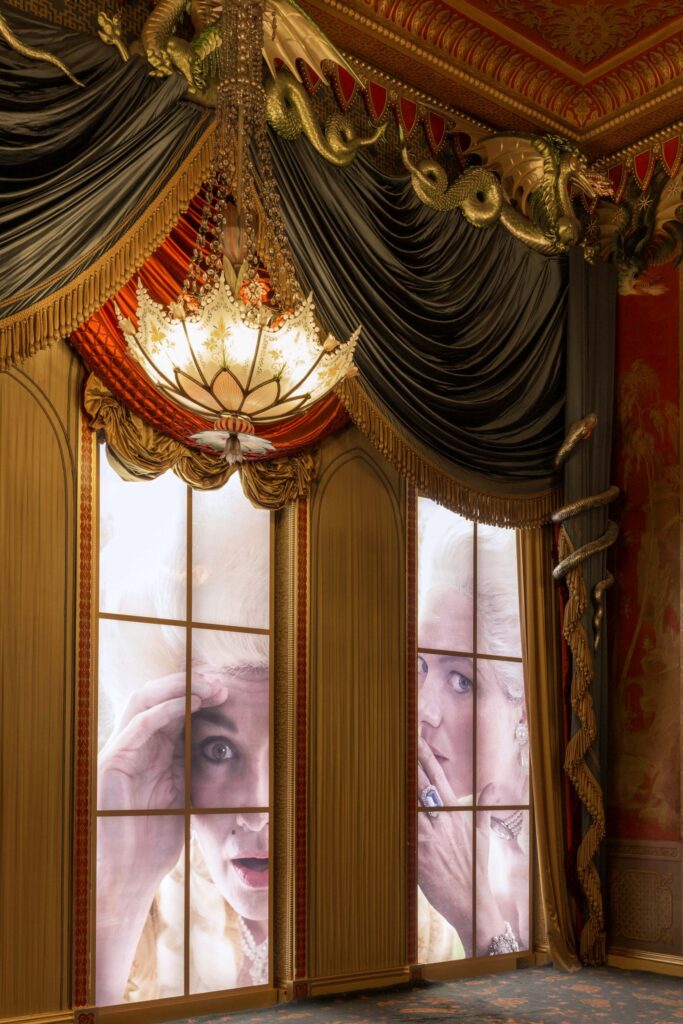

The Brighton Pavilion was built by Prince Regent, George IV. He was a terrible, terrible human being. He was waiting to be king for so long, but he was spending all this money. And he basically had this building that looks like a mini-Taj Mahal from the outside. The interior is a car crash of what he thought oriental art was. And so it’s a real, sort of overwhelming place and space to be in. And I remember them coming in and saying, ‘You know, can you get involved in the space?’ And I’m thinking, ‘I don’t even know where to start with any of this, like, I’ve got no idea!’ But I ended up being more interested in the character and in him as a person. He was quite a flamboyant character; he spent loads of money; he really liked to drink and go hard, and he was alive during a time when political satire in this country was first being born.

So he went from being at a point where people couldn’t say anything about the royal family, to this shift in what was legally allowed to be said in newspapers. And suddenly these cartoons were popping up of him in the newspapers, you know, comic strips depicting him as a kind of whale or as this kind of, you know; he’d go out and people kind of really scrutinized his behaviour. Prostitutes and such. He’d also not been able to marry the woman that he loved, and then so his parents went on this big rant, and so he was also, forced to marry somebody else. And he lost a daughter. And a compilation of all these things led to him going, basically, slightly insane, I think. And so he ended up being quite reclusive in that building. To the extent that there was even a secret tunnel built under the pavilion, that went between the building to his nearby stables so that he didn’t have to go into the royal court, because he didn’t want to be seen.

And so those windows were meant to be full of courtiers outside, and they were meant to reflect on someone who feels a bit like they’re very much the subject of public scrutiny. I made them huge, as I wanted the viewers to sense that they were being watched, like George IV had been, when he was there. Because when he first was there—that’s an important point—when he was first there; this music room, he used, this is disgusting, he used to throw lavish parties there, but there were no gates around it, so it meant people who were much much poorer than him, to watch. Very voyeuristic.

And then it shifted, so it went from being, ‘look at me’, you know, da-da-da-da; to suddenly him then having a sort of change of heart. So that was what that piece, there, was all about. But it was quite good fun to do that one, because I couldn’t find any… there were no portraits of people in the building. There was a lot of ornate interior design, but he didn’t… he didn’t commission any paintings of himself.

It was quite fun, the end of that one. I walked in and suddenly there were these big light boxes that you… It felt like you were being watched, as opposed to getting a nice view.

JB

I mean, so much of what people… I mean, first of all, so much of what happens around the Old Masters; people are often just either turned off by them, or don’t have the knowledge or the history or the desire to learn much more about them, beyond a surface-level image. And then, just because of their history and the valuation, there’s always this seriousness to them. So I really appreciate that you… that your work… How do I say this…. That you’re aware of the history of them. You know what they are, but your take on them is not focused on that. And you can also see that you bring a certain comedy to them that isn’t probably evident without speaking with you. And I really like that aspect of the few things that we talked about, in relation to your process and ideas. It’s a through line because to switch it around; I think you can only get that level of consciousness around these topics and these literal objects in the world, by first appreciating them, and actually understanding them. Only then can you go beyond them, as you do.

Personally, growing up in the USA, you’re not surrounded by, like, the weight of the British Empire. There’s not, cast iron fences and, you know, the beauty of London, everywhere in America, in each city. They tried their best with the City Beautiful movement, cultivating Englishness. Nor is there all this, like, art, in the nation’s collections in the same way, scattered throughout the country, like it is in England. So I think to even get to that level of appreciation, to be able to riff on them the way you have, takes a certain sense of appreciation of history, and an awareness of it, but an ability to not revere it, too, too much.

You mentioned it before; but could elaborate a bit about your work that, in its own way, recalls the scenes of Vermeer?

MB

The thing about the Vermeers, which is quite interesting given that you’re where you are, in Amsterdam, is that I think the other thing that was probably noted at the time was that I’ve come back to him more than any of the other painters. I hear this a lot from other people. Because the lighting in the work; it’s just so strong. But he also, and I guess other people, I know that this has been written about a lot too, but it’s definitely important…

He didn’t depict royalty.

So with Vermeer, when you’re really analyzing that stuff in his work; the lighting’s obviously beautiful; but it’s also just that it’s often an intimate moment with a very domestic situation.

And again, I’ve come from a family of five girls.

I’m not saying that we’re domestic in that way, but I think we’re all mothers now, and I think in a way his work has a quietness to them. And they have an intimacy to them in a slightly different way than some of the other Old Master paintings. It’s not like, ta-da!; you know? It’s not flags and crowns and royalty, and they’re not often dripping in pearls.

It’s a different observation and it is an observation of maybe a more intimate activity.

In his work, the woman’s often sort of gazing, or she’s kind of lost in her own head. And I think that’s particularly relevant to me, having so many sisters, and using my own family members as sitters in my work, means that I’ve been able to sort of… put them into that role quite comfortably, because they sort of sit there anyway, or I’ve observed them in that same way, just naturally, anyway.

This is what I mean when I say that my work is not just about a situation that I stage, with props or people, where I have this idea and then figure out who can I find that fits the look; and pop them in there so I can, you know, snap my image with my camera and then poof—here’s my work to sell. It’s not that.

JB

That’s what I mean about the whole process being the work. It’s not just: ‘Who can I find that looks like this world in a Vermeer painting?’ It’s really intimate and meaningful, so that’s also part of the process.

MB

Yeah; for sure. The other thing is, I don’t know if I mentioned this yet; but there’s also, I suppose, on a technical level, a lot I do. I do retouch my images. But nothing’s there that wasn’t in the photograph. But they’re often a composite. So the other thing about getting that look is sort of playing with the idea of, ‘Is it real; fake? Is it a painting; or is it a photograph?’

I print them matte. I like the idea that when they are on display, again, one could be left going, ‘Sorry, what is it that I’m looking at?’ And I think part of it is slightly uncanny; unsure of what it is that you’re looking at, is down to the fact that when I do them in composites, I’ll put things in focus that shouldn’t be in focus. Obviously, you’ve got a camera, you can only focus on a face, or you can’t get the background and you can get the foreground in focus. So each image is normally a composite. The works, when they are really big; the actual image file would be made of upwards of 200 pictures, but only in order to get everything that I want there in focus. Otherwise, I’d have to change the focus point around the set, and then put it back together. And so when I do this, it suddenly stops looking like a photograph and more like a painting. When it comes to the Old Masters; the reason they look the way they do, is because everything is in focus. That’s why your eye travels around the canvas when looking at them. It’s all there.

So by nearing up the focus, so that things that shouldn’t be in focus are, it gives it that quality of being slightly unsure. Because it’s sort of like flatness; because it becomes sort of uniform. And so, I will keep something naturally out of focus, but I will also just cut them out, just in case, and it’ll be dialed up a little bit more, in focus, than they should be. But also, everything in the foreground of the pictures is always in focus, and then, so are the models, or model, and so are hands—because when I shoot, I tend to use a medium format camera. There’s no way I could get all that in one image. In the past, I’ve occasionally used a retoucher; but when I do it myself, it will take about three weeks, to do one picture.

JB

Dedication.

MB

Yeah; that’s how it works with that. People often say to me, even when they’re standing in front of me and they come into the studio or something, and they’ll go, ‘I like your paintings!’

But I can’t paint like that, honestly. Some people, indeed, can. Not me. I’m flattered that people assume that they’re paintings, because then they might just think that I’m really good. Ha! I’m really good at what I do, for sure. But people remain surprised.

At the moment, I’m actually looking at how to get back to this 2D, 3D thing.

When I went to art school, I didn’t realize that the majority of my working life now as an artist is like, heavy admin. Communication with the galleries on a price; or I’m doing something for a museum. If you want to be an artist, and you want it as your life and career, you really need to want it, in that sense, to also sustain you, financially. That’s something that’s always been quite important to me, coming from my family of artists. I especially realized that in pandemic lockdowns; I don’t think I’m somebody that goes to the studio and humbly works around, you know, tinkering and making and not being sure of the output.

If I couldn’t afford my life; if it didn’t pay for itself, and the studio, I think I’d find it quite hard to justify doing it. I suppose growing up in an arty family permitted me to do my work. I don’t think about sales when I’m doing my work. And I don’t think about sales when I’m dealing with scale. I couldn’t shift half the things that I made, in scale, without knowing lots of mansion owners. I’m flattered when things sell. Like, I’m genuinely flattered when people buy my work. It’s been a very nice feeling. It still surprises me.

JB

With your pearl series, for instance, I’m sure you probably had like, conservative people who think they’re progressive; and I’m sure you’ve had people that see straight through it, right away, for what it is.

MB

Like, I’m never really sure why people acquire my work.

Once I had one of those pearl pieces that sold, and I had to go and put it up in this gorgeous place; a very nice, very, very nice house in London. I don’t normally go and install my work for my collectors, but they requested that I come and they bought a number of my pieces. So in a way, I think it was probably that they wanted to meet me. The wife was very interested in my work. And so as I’m putting the pearls in the frame and zipping it up and installing everything, snapping it all together—it was one of these works where she was chained to the wall, or something—her husband came in as I was working.

So he walked in and said, ‘Darling, what’s this about?’ And then the wife, who fully understood the work, kind of was like, ‘Oh, it’s about this… you know; this little woman being shackled to her own advantages.’ And he said, ‘Darling, do you think that’s appropriate for a house with kids in it; we have girls.’ And I just thought to myself: I am walking out of this room, slowly; this is absolutely a conversation that you need to have without me; you have definitely already acquired the works from me. And so I have certainly had some interesting situations happen before, in relation to my work, where there’s been a genuine misunderstanding about the content.

It’s quite funny when these types of scenarios happen; more fun than anything, really.

But yeah, there’s a few more of these, types of amazing moments in my life, as an artist.