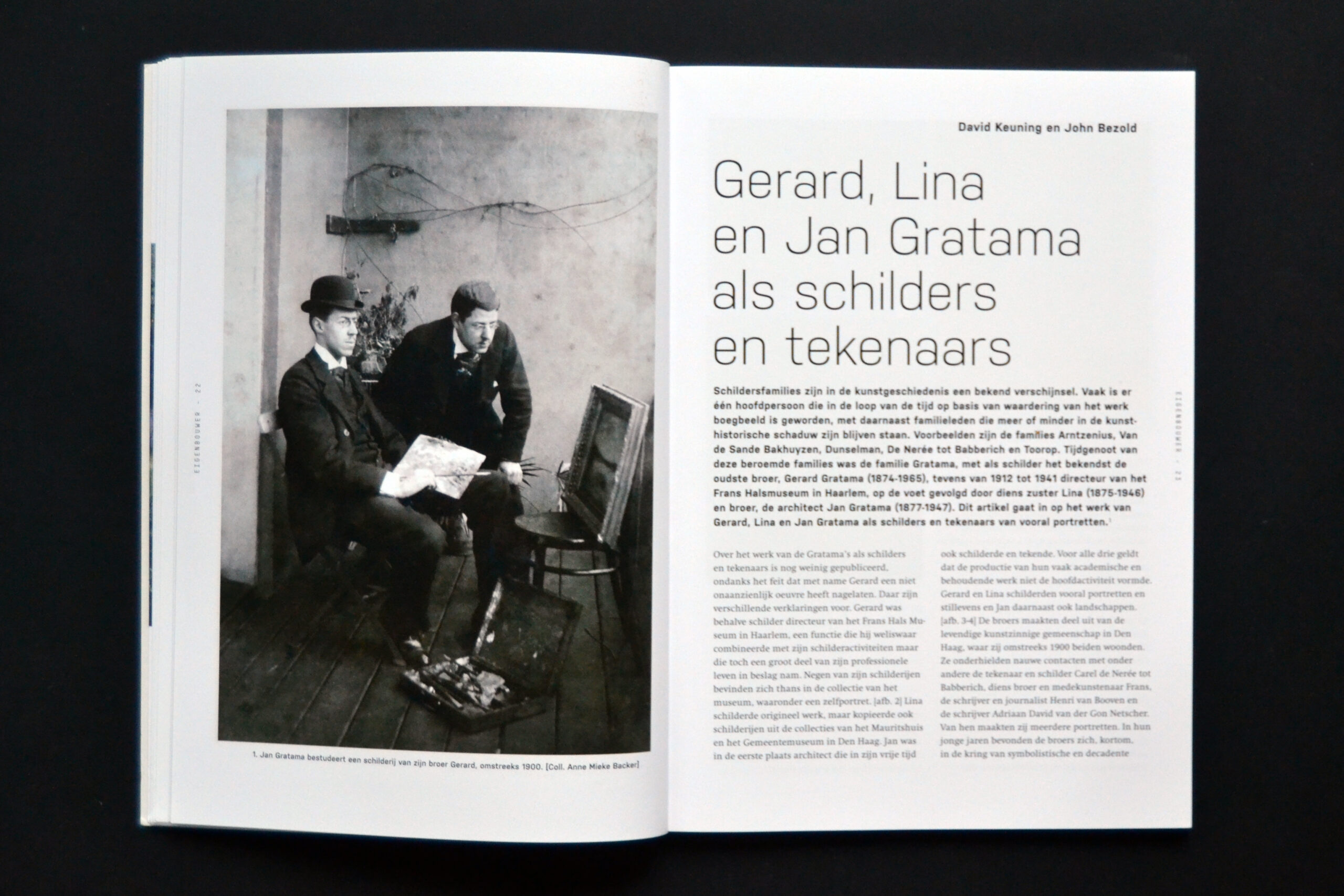

Painting families are a familiar phenomenon in art history. There is often one protagonist who has become a figurehead over time based on an appreciation of the work, along with family members who have remained more or less in the art historical shadow. Examples include the Arntzenius, Van de Sande, Bakhuyzen, Dunselman, De Nerée tot Babberich, and the Toorop families. Contemporaries of these famous families were the Gratama family, with the painter best known as the eldest brother, Gerard Gratama (1874-1965), who was also the director of the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem from 1912 to 1941, closely followed by his sister Lina (1875-1946) and brother, the architect Jan Gratama (1877-1947). This article examines the work of Gerard, Lina, and Jan Gratama as painters and draughtsmen, especially portraits.1

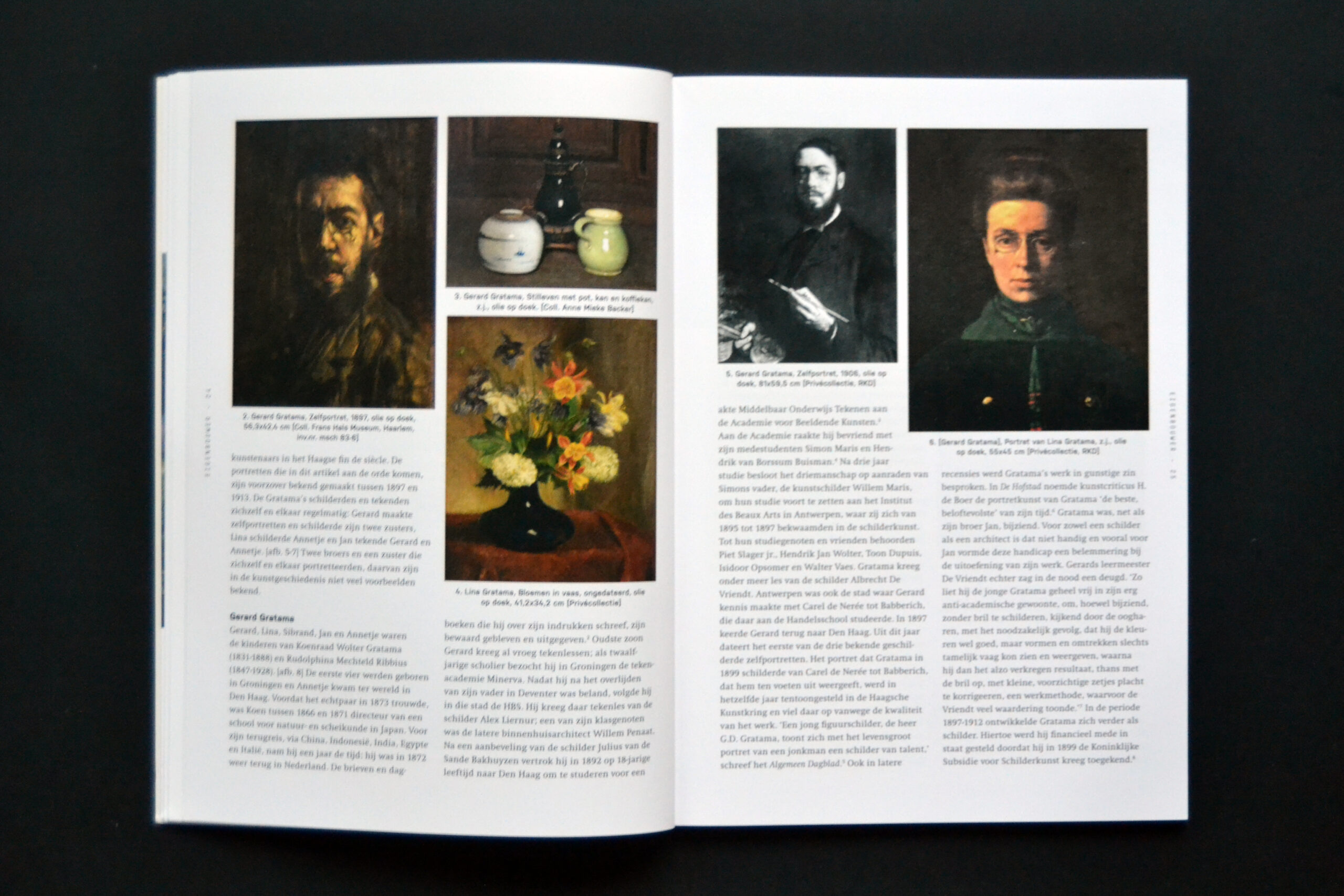

Little has been published about the work of the Gratamas as painters and draughtsmen, despite the fact that Gerard in particular left behind a not inconsiderable body of work. There are several explanations for this. In addition to being a painter, Gerard was director of the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem, a function which, although he combined with his painting activities, still occupied a large part of his professional life. Nine of his paintings are currently in that museum’s collection, including a self-portrait. Lina painted original work, but also copied paintings from the collections of the Mauritshuis and the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague. Jan was primarily an architect who in his spare time also painted and drew. For all three, the production of their often academic and conservative work was not the main activity. Gerard and Lina mainly painted portraits and still lifes and Jan also painted landscapes. The brothers were part of the lively artistic community in The Hague, where they both lived around 1900. They maintained close contacts with, among others, the draughtsman and painter Carel de Nerée tot Babberich, his brother and fellow artist Frans, the writer and journalist Henri van Booven and the writer Adriaan David van der Gon Netscher. They made several portraits of them. In their younger years, the brothers found themselves, in short, in the circle of symbolist and decadent artists in the Hague fin de siècle. As far as is known, the portraits discussed in this article were made between 1897 and 1913. The Gratamas regularly painted and drew themselves and each other: Gerard made self-portraits and painted his two sisters, Lina painted Annetje, and Jan drew Gerard and Annetje. Two brothers and a sister who portrayed themselves and each other, of which there are not many examples known in art history.

Gerard Gratama

Gerard, Lina, Sibrand, Jan, and Annetje were the children of Koenraad Wolter Gratama (1831-1888) and Rudolphina Mechteld Ribbius (1847-1928). The first four were born in Groningen and Annetje came into the world in The Hague. Before the couple married in 1873, Koen was director of a school of physics and chemistry in Japan between 1866 and 1871. For his return trip, via China, Indonesia, India, Egypt, and Italy, he took a year: he was back in the Netherlands in 1872. The letters and diary-books he wrote about his impressions there, have been preserved and published.2 The eldest son Gerard received drawing lessons at an early age; as a 22-old pupil he attended the Minerva drawing academy in Groningen. After ending up in Deventer after the death of his father, he attended the HBS in that city. There he received drawing lessons from the painter Alex Liernur; one of his classmates was the later interior designer Willem Penaat. Following a recommendation from the painter Julius van de Sande Bakhuyzen, he left for The Hague in 1892 at the age of 18, to study for a Certificate in Secondary Education Drawing at the Academy of Visual Arts.3. At the Academy, he became friends with fellow students Simon Maris and Henvan Borssum Buisman.4 After three years of study studies, the trio decided, on the advice of Simon’s father, the painter Willem Maris, to continue their studies at the Institut des Beaux Arts, in Antwerp, where they studied painting from 1895 to 1897. Their fellow students and friends included Piet Slager Jr., Hendrik Jan Wolter, Toon Dupuis, Isidoor Opsomer, and Walter Vaes. Gratama received lessons from the painter Albrecht De Vriendt, among others. Antwerp was also the city where Gerard became acquainted with Carel de Nerée tot Babberich, who studied at the trade school there. In 1897, Gerard returned to The Hague. From this year dates the first of the three known self-portraits. The portrait Gratama painted of Carel de Nerée tot Babberich in 1899, depicting him full-length, was exhibited at the Haagsche Kunstkring in the same year and stood out there because of the quality of the work. ‘A young figure painter, Mr. G .D. Gratama, shows himself a painter of talent with the life-size portrait of a young man’, wrote the Algemeen Dagblad.5 Also in later reviews, the commentary was favorable of Gratama’s work. In De Hofstad, art critic H. de Boer called Gratama’s portraiture, ‘the best, most promising’ of its time.'6 Gratama, like his brother Jan, was nearsighted. For both a painter and an architect, this is not convenient, and for Jan in particular, this handicap constituted a hindrance in the performance of his work. Gerard’s teacher De Vriendt, however, saw a virtue in necessity. ‘Thus he gave the young Gratama complete freedom in his very anti-academic habit, although nearsighted, to paint without glasses, looking through the eyelids, with the necessary result that he could see and reproduce the colors well, but shapes and outlines only rather vaguely, after which he could then reproduce the result thus obtained, which he could then paint without glasses. He would then correct the result thus obtained, now with his glasses on, with small, careful strokes, a working method, for which de Vriendt showed great appreciation.’ In the period 1897-1912 Gratama developed further as a painter.7 He was financially enabled to do so by being awarded the Royal Grant for Painting in 1899.8

Gratama’s work had little in common with the Hague School and Impressionism, but since leaving Antwerp he had abandoned the academic tradition of the Beaux-Arts. Instead, he developed a much simpler visual language. The Hollandsche Revue related this to the ‘precise, pure and clear’ of the Japanese works of art that his father had brought back from his stay abroad. In addition to his painting practice, he was a teacher of drawing at the Academy of Visual Arts for three years and a teacher of art history at the Nederlandsch Lyceum, both in The Hague.9 He also gave private lessons in painting in his own studio, mainly to women from and living in, The Hague.

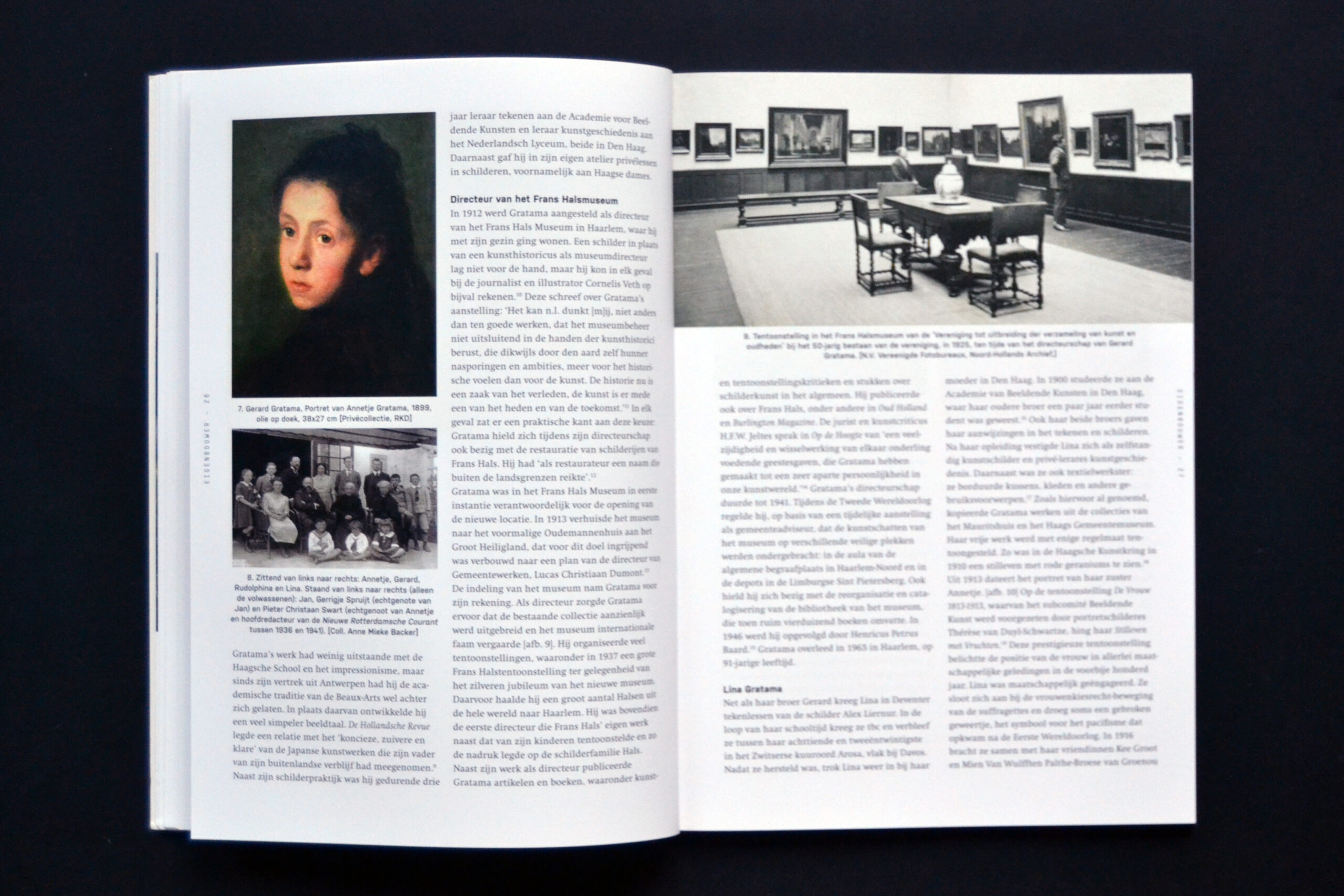

Director of the Frans Hals Museum

In 1912, Gratama was appointed director of the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem, where he went to live with his family. A painter rather than an art historian as museum director was not an obvious choice, but at least the journalist and illustrator Cornelis Veth applauded him.10 The latter wrote the following about Gratama’s appointment: ‘In my opinion, it cannot but be beneficial that the museum management does not rest exclusively in the hands of art historians, who often by the very nature of their investigations and ambitions, feel more for history than for art. History is a matter of the past, art is also a matter of the present and of the future.'11 In any case, there was a practical side to this choice: during his directorship, Gratama was also involved in the restoration of paintings by Frans Hals. He had, ‘as a restorer a name that reached beyond the borders of the country.'12 At the Frans Hals Museum, Gratama was initially responsible for opening the new location. In 1913 the museum moved to the former Oudemannenhuis, on the Groot Heiligland, which had been extensively remodeled for this purpose according to a plan by the director of Gemeentewerken, Lucas Christiaan Dumont.13 Gratama took charge of the layout of the museum. As director, Gratama ensured that the existing collection was significantly expanded and the museum gained international fame. He organized many exhibitions, including a major Frans Hals exhibition in 1937, to mark the silver jubilee of the new museum. For this, he brought a large number of Hals from all over the world to Haarlem. Moreover, he was the first director to exhibit Frans Hals’ own work alongside that of his children, thus emphasizing the Hals family of painters. In addition to his work as director, Gratama published articles and books, including arts exhibition critiques and pieces on painting in general. He also published on Frans Hals, including in Oud Holland and the Burlington Magazine. The lawyer and art critic H. F. W. Jeltes spoke in Op de Hoogte of, ‘a multiplicity and interaction of mutually nourishing gifts of mind, which have made Gratama a very distinct personality in our art world.'14 Gratama’s directorship [he was an advisor until 1946] lasted until 1941. During the Second World War, on the basis of a temporary appointment as a municipal advisor, he arranged for the museum’s art treasures to be housed in various safe locations: in the auditorium of the general cemetery in Haarlem-North and in the depots in the Limburg Sint Pietersberg. He also engaged in the reorganization and catalogization of the museum’s library, which at the time comprised over four thousand books. In 1946 he was succeeded by Henricus Petrus Baard.15 Gratama died in Haarlem in 1965, at the age of 91.

Lina Gratama

Like her brother Gerard, Lina received drawing lessons in Deventer from the painter Alex Liernur. During her schooling, she contracted tuberculosis and between the ages of 18 and 22 stayed in the Swiss spa town of Arosa, near Davos. After she recovered, Lina moved back in with her mother in The Hague. In 1900 she studied at the Academy of Visual Arts in The Hague, where her older brother had been a student a few years earlier16 Both her brothers also gave her instructions in drawing and painting. After her education, Lina established herself as a self-employed painter and private teacher of art history.17 She was also a textile worker: she embroidered cushions, rugs, and other such objects. As mentioned above, Gratama copied works from the collections of the Mauritshuis and the Haags Gemeentemuseum. Her free work was exhibited with some regularity. A still life with red geraniums was exhibited at the Haagsche Kunstkring in 1910.18 The portrait of her sister Annetje dates from 1913. At the exhibition, ‘De Vrouw 1813-1913’, of which the subcommittee Visual Arts was chaired by portrait painter Thérèse van Duyl-Schwartze, hung her Still Life with Fruits.19 This prestigious exhibition highlighted the position of women in all sorts of social ranks over the past hundred years. Lina was socially engaged. She joined the suffragettes’ women’s suffrage movement and sometimes wore a broken rifle, the symbol of the pacifism that emerged after the First World War. In 1916, she and her friends Kee Groot and Mien Van Wulfften Palthe-Broese van Groenou issued a political revue under the name Kakelen is geen Eieren leggen. Parodie op de behandeling van artikel 80.20 In a text written in rhyme, a humorous commentary was given on the contents of article 80 of the Dutch Constitution, which established in 1887 that the right to vote was reserved for men.21 The revue was shown several times, using pictures from various magazines and statements by politicians from 1916. In 1921, Lina Gratama was on the founding board of the association Club Building for Women. The renovation of a distinguished building on Hooge Nieuwstraat in The Hague was designed by her brother Jan. The rooms in the front house were converted into a dining room, reading room, conversation room, and a guest room, among other things. In the former stable in the rear house, Gratama designed an auditorium with three hundred chairs in Amsterdam School style under an old open-worked roof structure. The Bouwblad van het Vaderland called the result ‘the most beautiful meeting room in The Hague.'22 After the clubhouse was completed, regular exhibitions were also held here where Lina’s work was was on display. In 1927 the Painting Association ODIS (Ons doel is schoonheid) arose from the Club for Women. Lina’s work could also be admired with some regularity in the exhibitions organized by this society, including the Haagsche Kunstkring (Hague Art Society) during the 1930s. In 1939 her painting Greenhouse from the Horticultural School in Rijkswijk, was on display in the exhibition ‘Onze Kunst van Heden’ in the Rijksmuseum, together with three paintings by her older brother.23 Incidentally, this horticultural school most probably concerned the horticultural school for girls on the Vreedenburghweg in Rijswijk designed by her brother Jan and his partner Samuel de Clercq in 1904 and 1905. This villa, commissioned by the women, J. Hingst and C. Pompe, was built with school rooms on the first floor and was equipped with a nursery.24 Nothing is known of Lina’s activities during World War II. She died in 1946, at the age of 71.

Jan Gratama

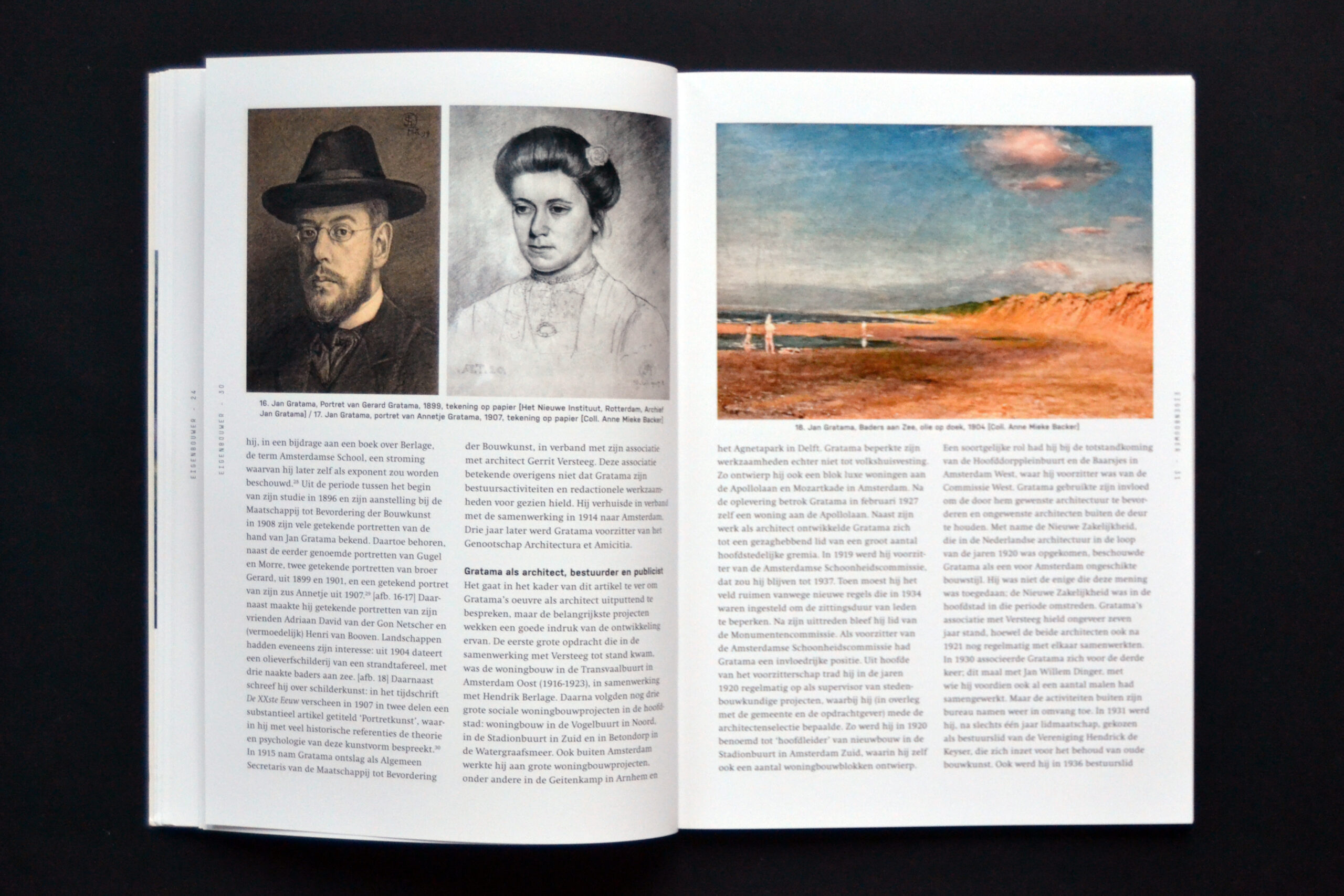

Although Jan was good at drawing and painting, and initially wanted to become a painter like his older brother and sister, he chose to study naval architecture at the Polytechnic School in Delft.25 At the time, this required a preliminary degree in mechanical engineering, which he began in 1896. However, this study soon proved to be ‘too dry’ for him, so he switched almost immediately to civil engineering.26 After three years of civil engineering, on the advice of several professors, he switched to architecture, in which he graduated in 1902. His teachers included professors Eugen Gugel and Jaap Klinkhamer. Gratama drew portraits of Gugel and his assistant Gerrit Jan Morre that were published in the Delftsche Studenten Almanak, a publication of the Delftsch Studentencorps.

Gratama was also editor of the Delft student magazine In den Nevel, a literary journal with a socialist character under the motto: ‘We in the Nebula, but in us the eternal light of the Ideal.’ Three volumes of the magazine appeared, the first of which was provided with a cover by Jan Toorop in 1897. His co-editors included his friend and fellow student Samuel de Clercq and civil engineering student Theo van der Waerden, later a member of the SDAP Lower House. Then, in 1898, the first issue of the Studenten Weekblad appeared, which in time more or less replaced In den Nevel. Gratama was on the editorial board of the first two issues, together with, among others, Willem Albarda, who would later also become a member of parliament for the SDAP, and the hydraulic engineer Victor de Blocq van Kuffeler. After his graduation, The Hague municipal architect Adam Schadée Gratama was hired as a draughtsman at the Public Works Department. He did not like this position very much and stayed there for only a year. He then became assistant to the Delft professor of architecture Henri Everts, whom he helped with drawing classes, preparing lectures, and organizing the library. Around 1901, Gratama moved from The Hague back to Delft and then in 1904 to Rijswijk, where he started a small private architectural practice with his college friend De Clercq. He maintained the assistantship in Delft. Gratama’s collaboration with De Clercq did not last long; soon he shifted his attention from architectural practice, to the association life. The reason for this was unfortunate: Gratama was diagnosed with ‘a serious disease’ in his right eye, making him severely nearsighted. In 1908 Gratama was appointed General Secretary of the Society for the Advancement of Architecture.27 At almost the same time he became editor of the Bouwkundig Weekblad. In that journal, Gratama developed into a keen analyst of contemporary architecture. He also published widely elsewhere. For example, in a contribution to a book on Berlage, he coined the term ‘Amsterdam School’, a movement of which he himself would later be considered an exponent.28 From the period between the start of his studies in 1896 and his appointment at the Maatschappij tot Bevordering der Bouwkunst in 1908, many drawn portraits by Jan Gratama are known. These include, in addition to the aforementioned portraits of Gugel and Morre, two drawn portraits of brother Gerard, from 1899 and 1901, and a drawn portrait of his sister Annetje from 1907.29 In addition, he made drawn portraits of his friends Adriaan David van der Gon Netscher and (presumably) Henri van Booven. Landscapes also had his interest: from 1904 dates an oil painting of a beach scene, with three naked bathers by the sea. He also wrote about painting: in 1907 the magazine De XXste Eeuw published a substantial two-volume article entitled ‘Portrait Art’, in which he discussed the theory and psychology of this art form with many historical references.30 In 1915 Gratama resigned as General Secretary of the Maatschappij tot Bevordering der Bouwkunst der Bouwkunst, in connection with his association with architect Gerrit Versteeg. However, this association did not mean that Gratama abandoned his board activities and editorial work. In connection with the association, he moved to Amsterdam in 1914. Three years later Gratama became president of the Genootschap Architectura et Amicitia.

Gratama as Architect, Administrator, and Publicist

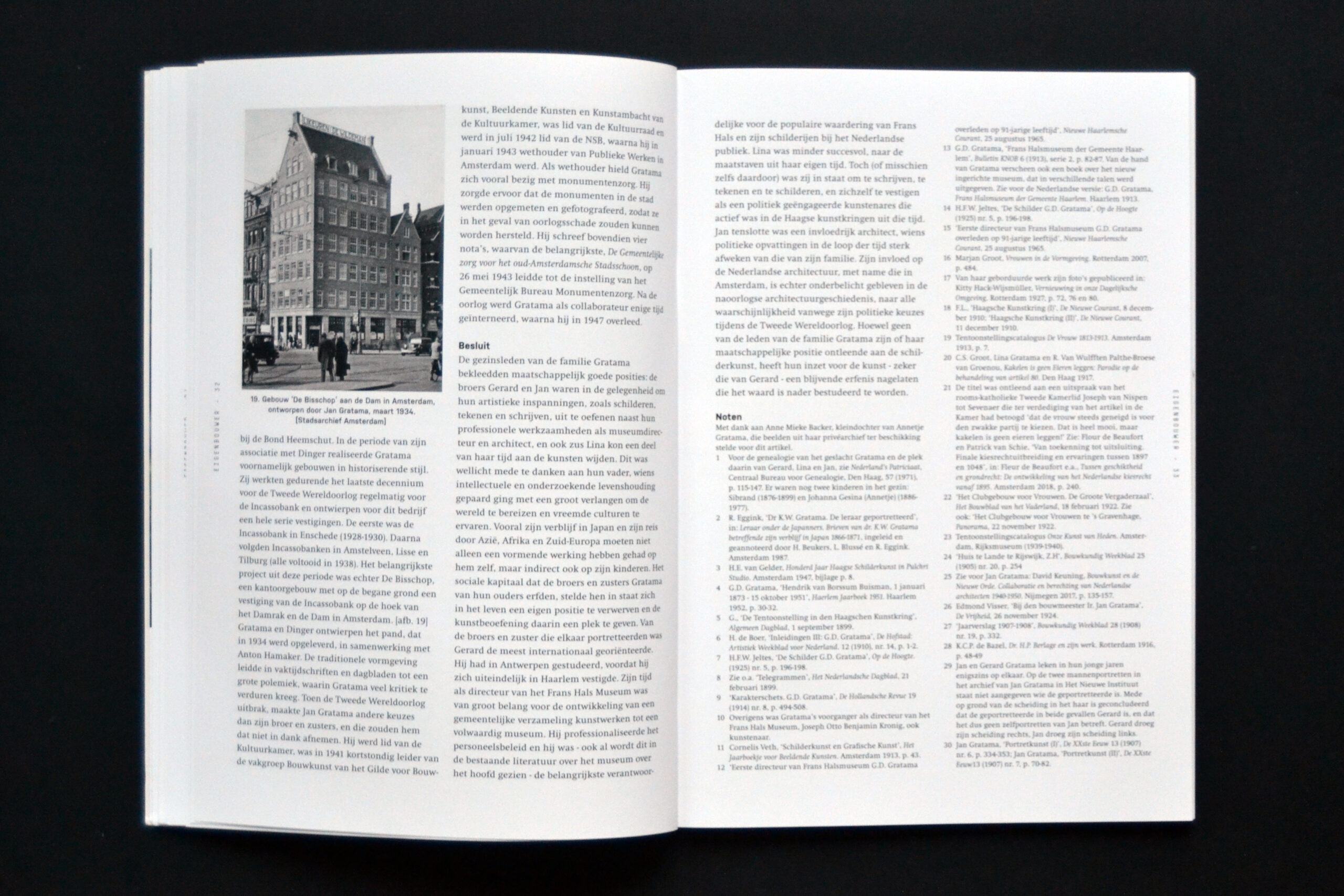

For the purposes of this article, it would go too far to discuss Gratama’s oeuvre as an architect exhaustively, but the most important projects give a good impression of its development. The first major commission realized in collaboration with Versteeg was the housing development in the Transvaal neighborhood in Amsterdam East (1916-1923), in collaboration with Hendrik Berlage. This was followed by three more major social housing projects in the capital city: housing in the Vogelbuurt in North, in the Stadionbuurt in South, and in Betondorp in the Watergraafsmeer area. He also worked outside Amsterdam on large housing projects, including the Geitenkamp in Arnhem and the Agnetapark in Delft. However, Gratama did not limit his work to public housing. For example, he also designed a block of luxury homes on Apollolaan and Mozartkade in Amsterdam. After completion, Gratama himself moved into a home on Apollolaan in February 1927. In addition to his work as an architect, Gratama developed into Gratama developed into an authoritative member of many metropolitan bodies. In 1919 he became chairman of the Amsterdam Beauty Commission, a position he held until 1937. Then he had to resign because of new rules that were introduced in 1934 to limit the term of office of members. After stepping down, he remained a member of the Monument Commission. As chairman of the Amsterdam Beauty Commission, Gratama had an influential position. By virtue of his chairmanship, in the 1920s he regularly acted as supervisor of urban architectural projects, helping to determine (in consultation with the municipality and the client) the selection of architects. For example, in 1920 he was appointed ‘head leader’ of new construction in the Stadionbuurt in Amsterdam South, in which he himself also designed a number of housing blocks. He had a similar role in the creation of the Hoofddorpplein neighborhood and the Baarsjes in Amsterdam West, where he was chairman of the Commission West. Gratama used his influence to promote the architecture he desired and keep out undesirable architects. In particular, the ‘New Objectivity’, which had emerged in Dutch architecture during the 1920s, Gratama considered this style of architecture unsuitable for Amsterdam. He was not the only one who held this view; New Objectivity was controversial in the capital at the time. Gratama’s association with Versteeg lasted for about seven years, although the two architects continued to work together regularly after 1921. In 1930 Gratama associated himself for the third time; this time with Jan Willem Dinger, with whom he had also worked several times before. But the activities outside his office again increased in scope. In 1931, after only one year of membership, he was elected a board member of the Hendrick de Keyser Association, which is dedicated to the preservation of old architecture. Also in 1936, he became a board member at the Bond Heemschut. During the period of his association with Dinger, Gratama realized mainly buildings in a historicizing style. They regularly worked for the Incassobank during the last decade before World War II and designed a whole series of branches for this company. The first was the Incassobank in Enschede (1928-1930). This was followed by Incassobanks in Amstelveen, Lisse, and Tilburg (all completed in 1938). The most important project of this period, however, was De Bisschop, an office building with an Incasso Bank branch on the ground floor at the corner of the Damrak and the Dam in Amsterdam. Gratama and Dinger designed the building, which was completed in 1934, in collaboration with Anton Hamaker. The traditional design led to a major polemic in trade journals and newspapers, in which Gratama faced much criticism. When World War II broke out, Jan Gratama made different choices than his brother and sisters, and they would not thank him. He became a member of the Kultuurkamer, and in 1941 was briefly the leader of the professional group Bouwkunst van het Gildevoor Bouw Art, Visual Arts and Art Craft of the Kultuurkamer, was a member of the Kultuurraad and joined the NSB in July 1942, after which he became alderman of Public Works in Amsterdam in January 1943. As an alderman, Gratama was primarily concerned with monument preservation. He made sure that monuments in the city were measured and photographed so that they could be repaired in case of war damage. He also wrote four memos, the most important of which, ‘De Gemeentelijke zorg voor het oud-Amsterdamsche Stadsschoon’, on 26 May 26 1943, led to the establishment of the Municipal Bureau for the Preservation of Monuments. After the war, Gratama was interned for some time as a collaborator, after which he died in 1947.

Conclusion

The family members of the Gratama family held good positions socially: brothers Gerard and Jan were able to pursue their artistic endeavors, such as painting, drawing, and writing, in addition to their professional work as museum directors and architects, and sister Lina was also able to devote some of her time to the arts. This was perhaps due in part to their father, whose intellectual and inquisitive attitude to life was accompanied by a great desire to travel the world and experience foreign cultures. In particular, his stay in Japan and his travel through Asia, Africa, and Southern Europe must have had a formative effect not only on him himself, but also indirectly on his children. The social capital that the Gratama brothers and sisters inherited from their parents enabled them to their own position in life and to give art a place within it. Of the siblings who portrayed each other, Gerard was the most internationally oriented. He had studied in Antwerp before eventually settling in Haarlem. His time as director of the Frans Hals Museum was instrumental in developing a municipal collection of artworks into a full-fledged museum. He professionalized the personnel policy and he was—even though this is overlooked in the existing literature about the museum—the main person responsible for the popular appreciation of Frans Hals and his paintings among the Dutch public. Lina was less successful, by the standards of her own time. Yet (or perhaps even because of it) she was able to write, draw, and paint, and establish herself as a politically engaged artist who was active in The Hague art circles of the time. Finally, Jan was an influential architect whose political views diverged greatly from those of his family over time. However, his influence on Dutch architecture, especially that in Amsterdam, has remained understudied in postwar architectural history, in all likelihood because of his political choices during World War II. Although none of the members of the Gratama family derived his or her social position from painting, their commitment to art—certainly—has left a lasting legacy worthy of further study.

Originally published in Eigenbouwer 16, Nov. 2022.

Written together with David Keuning.

Thanks to Anne Mieke Backer, granddaughter of Annetje Gratama, who provided images from her private archive for this article.

- For the genealogy of the Gratama family and the place in it of Gerard, Lina and Jan, see: Nederland’s Patriciaat, Centraal Bureau voor Genealogie, Den Haag, 57 (1971), 115-147. There were two other children in the family: Sibrand (1876-1899) and Johanna Gesina (Annetje) (1886-1977).↑

- Rudolphine Eggink, ‘Dr. K. W. Gratama. De leraar geportretteerd’, in: Leraar onder de Japanners. Brieven van dr. K.W. Gratama betreffende zijn verblijf in Japan 1866-1871, annotated by H. Beukers, L. Blussé, and R. Eggink. Amsterdam 1987.↑

- Henk Enno van Gelder, Honderd Jaar Haagse Schilderkunst in Pulchri Studio. Amsterdam 1947, appendix, 8.↑

- Gerard Gratama, ‘Hendrik van Borssum Buisman, 1 januari 1873-15 oktober 1951’, Haerlem Jaarboek 1951. Haarlem 1952, 30-32.↑

- ‘De Tentoonstelling in den Haagschen Kunstkring’, Algemeen Dagblad, 1 September 1899.↑

- H. de Boer, ‘Inleidingen III: G.D. Gratama’, De Hofstad: Artistiek Weekblad voor Nederland 12 no. 14, (1910): 1-2.↑

- H. F. W. Jeltes, ‘De Schilder G.D. Gratama’, Op de Hoogte, no. 5 (1925): 196-198.↑

- See, among others: ‘Telegrammen’, Het Nederlandsche Dagblad, 21 February 1899.↑

- ‘Karakterschets. G. D. Gratama’, De Hollandsche Revue 19, no. 8 (1914): 494-508.↑

- Gratama’s predecessor at the Frans Hals Museum, Joseph Otto Benjamin Kronig, was also an artist.↑

- Cornelis Veth, ‘Schilderkunst en Grafische Kunst’, Het Jaarboekje voor Beeldende Kunsten. Amsterdam 1913, 43.↑

- ‘Eerste directeur van Frans Hals Museum G. D. Gratama overleden op 91-jarige leeftijd’, Nieuwe Haarlemsche Courant, 25 August 1965.↑

- Gerard Gratama, ‘Frans Halsmuseum der Gemeente Haarlem’, Bulletin KNOB 6, series 2 (1913): 82-87. Gratama also published a book about the newly refurbished museum in several languages. For the Dutch version, see: Gerard Gratama, Frans Hals Museum der Gemeente Haarlem. Haarlem 1913.↑

- H. F. W. Jeltes,‘ De Schilder G. D. Gratama’, Op de Hoogte, no. 5 (1925): 196-198.↑

- ‘Eerste directeur van Frans Halsmuseum G. D. Gratama overleden op 91-jarige leeftijd’, Nieuwe Haarlemsche Courant, 25 August 1965.↑

- Marjan Groot, Vrouwen in de Vormgeving. Rotterdam 2007, 484.↑

- Photos of her embroidered work have been published in: Kitty Hack-Wijsmüller, Vernieuwing in onze Dagelijksche Omgeving. Rotterdam 1927, 2, 76, 80.↑

- F. L. ,‘Haagsche Kunstkring (I)’, De Nieuwe Courant, 8 December 1910; ‘Haagsche Kunstkring (II)’, De Nieuwe Courant, 11 December 1910.↑

- De Vrouw 1813-1913. Amsterdam 1913, 7.↑

- C. S. Groot, L. Gratama, and R. Van Wulfften Palthe-Broese van Groenou, Kakelen is geen eieren leggen: Parodie op de behandeling van artikel 80. Den Haag 1917.↑

- The title was taken from a statement by Roman Catholic Member of Parliament Joseph van Nispen tot Sevenaer who had argued in defense of the article that, ‘that woman is always inclined to choose the weak party. That is very nice, but clucking is not laying eggs!’ See: Flour de Beaufort and Patrick van Schie, ‘Van toekenning tot uitsluiting. Finale kiesrechtuitbreiding en ervaringen tussen 1897 en 1048’, in: Fleur de Beaufort (et al.), Tussen geschiktheid en grondrecht: De ontwikkeling van het Nederlandse kiesrecht vanaf 1895. Amsterdam 2018, 240.↑

- ‘Het Clubgebouw voor Vrouwen. De Groote Vergaderzaal’, Het Bouwblad van het Vaderland, 18 February 1922. See also: ‘Het Clubgebouw voor Vrouwen te ’s Gravenhage, Panorama, 22 November 1922.↑

- Onze Kunst van Heden. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (1939-1940).↑

- ‘Huis te Lande te Rijswijk, Z. H‘, Bouwkundig Weekblad 25, no. 20 (1905): 254.↑

- See, for Jan Gratama: David Keuning, Bouwkunst en de Nieuwe Orde. Collaboratie en berechting van Nederlandse architecten 1940-1950. Nijmegen 2017, 135-157.↑

- Edmond Visser, ‘Bij den bouwmeester Ir. Jan Gratama’, De Vrijheid, 26 November 1924.↑

- ‘Jaarverslag 1907-1908’, Bouwkundig Weekblad 28, no. 19 (1908): 332.↑

- K. C. P. de Bazel, Dr. H.P. Berlage en zijn werk. Rotterdam 1916, 48-49.↑

- Jan and Gerard Gratama looked somewhat alike in their younger years. The two male portraits in Jan Gratama’s archive at The New Institute do not indicate who the person portrayed is. Partly on the basis of the parting in the hair, it has been concluded that the person portrayed in both cases is Gerard, and that they are therefore not self-portraits of Jan. Gerard wore his parting on the right; Jan wore his parting on the left.↑

- Jan Gratama, ‘Portretkunst (I)’, De XXste Eeuw 13, no. 6 (1907): 334-353; Jan Gratama, ‘Portretkunst (II)’, De XXste Eeuw 13, no. 7 (1907): 70-82.↑