In an earlier edition of this magazine (Mark no. 21, page 55), I mused on the delight that Search’s observation tower in the Dutch village of Putten infused me with, as I climbed its stairs, passing mirrors, glass walls, and netted floors along the way to the top. At one point, only the netting separated me from the forest floor, 30 m below. What I took away from that observation tower in the woods, completed in 2009, was the playfulness that the ascent entailed. Was it due to the nature of the project (‘What isn’t it for?,’ I had asked at the time), or was it because of Search’s sensitive use of materials and color, and its recognition that architecture doesn’t always need a justification? After visiting Search’s most recent project–a former farmhouse extension located in a one-street village north of Amsterdam–I am able to report that the theme of playfulness continues to be strung throughout the firm’s work.

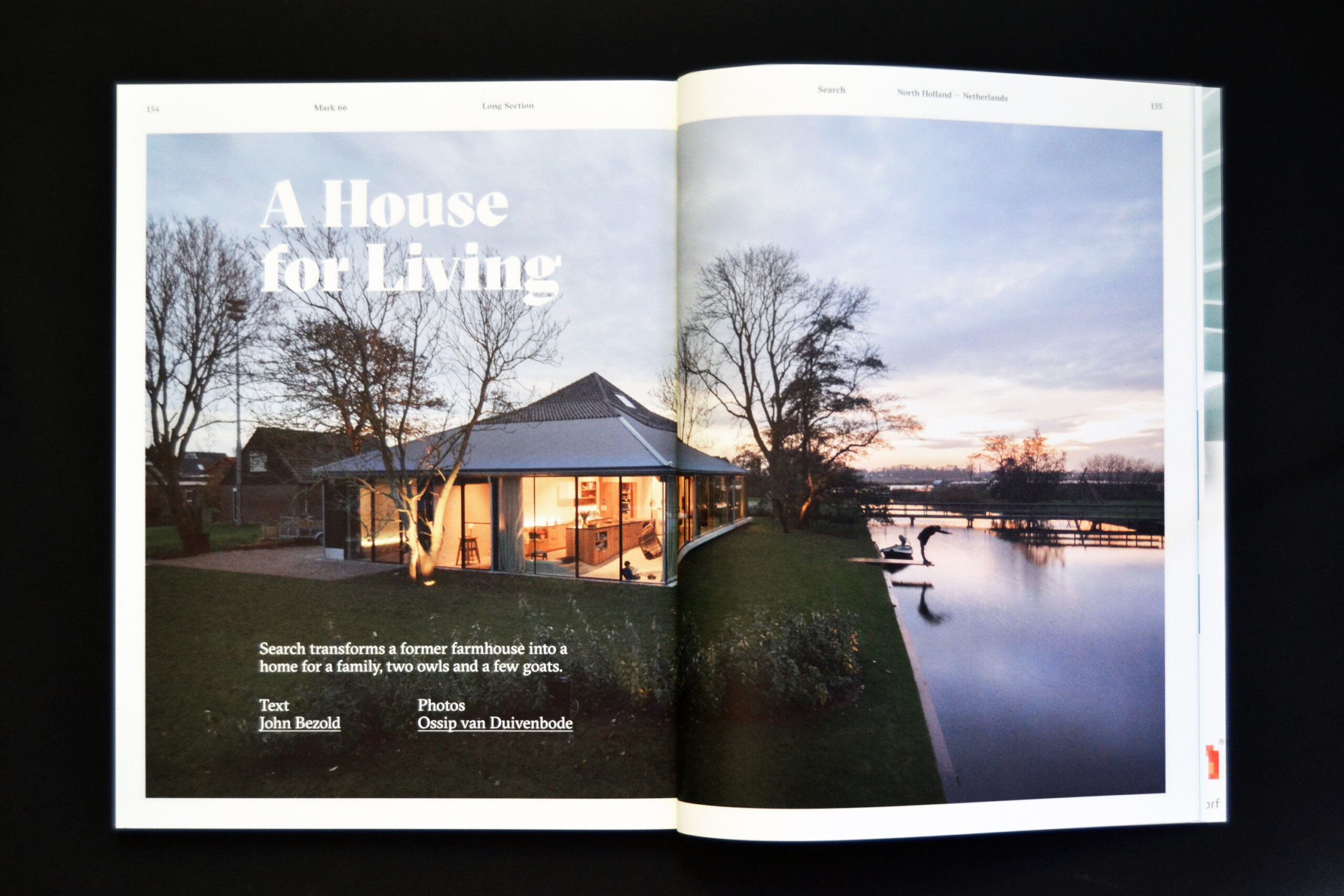

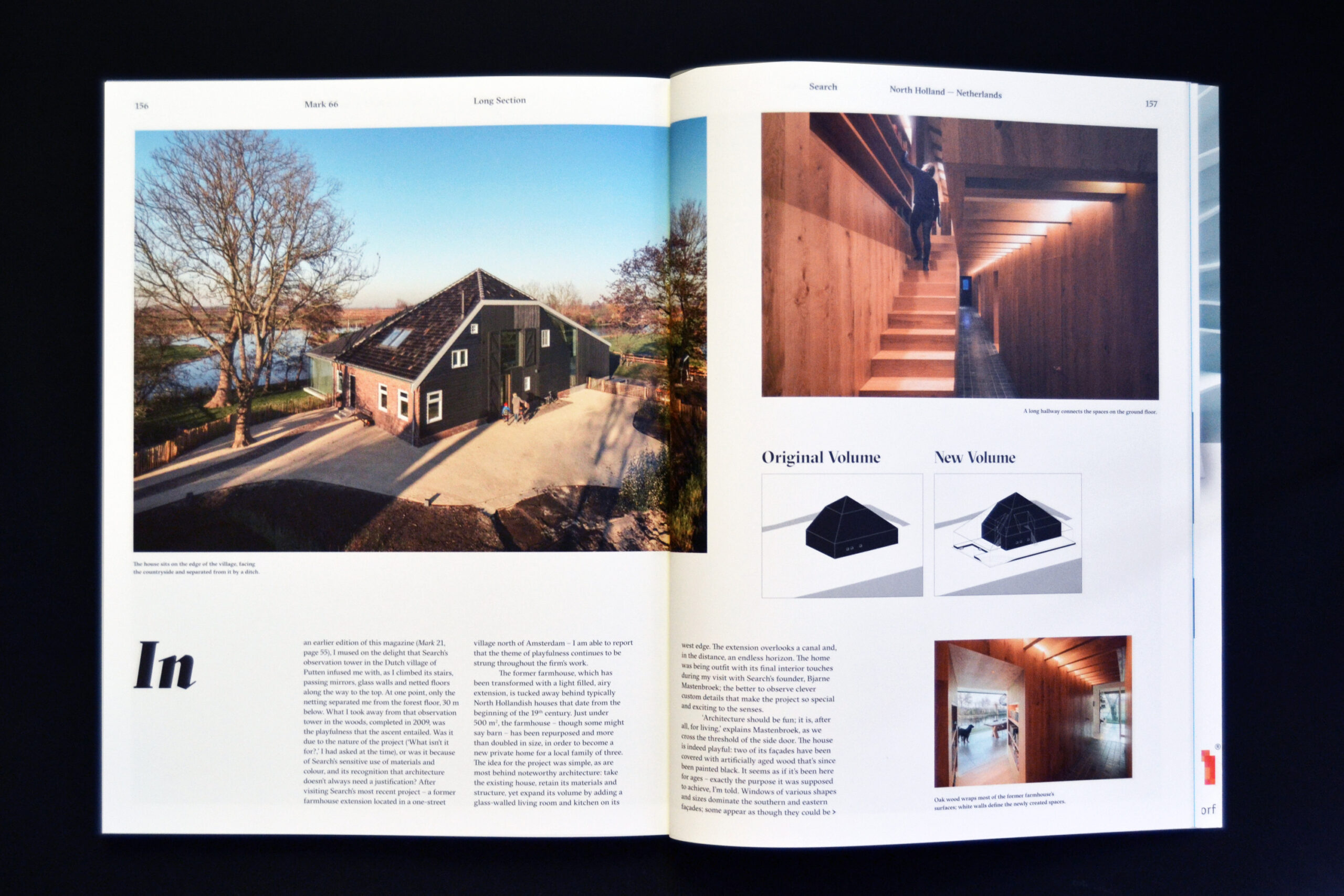

The former farmhouse, which has been transformed with a light filled, airy extension, is tucked away behind typically North Hollandish houses that date from the beginning of the 19th century. Just under 500 m2, the farmhouse–though some might say barn–has been repurposed and more than doubled in size, in order to become a new private home for a local family of three. The idea for the project was simple, as are most behind noteworthy architecture: take the existing house, retain its materials and structure, yet expand its volume by adding a glass-walled living room and kitchen on its west edge. The extension overlooks a canal and, in the distance, an endless horizon. The home was being outfit with its final interior touches during my visit with Search’s founder, Bjarne Mastenbroek; the better to observe clever custom details that make the project so special and exciting to the senses.

‘Architecture should be fun; it is, after all, for living,’ explains Mastenbroek, as we cross the threshold of the side door. The house is indeed playful: two of its façades have been covered with artificially aged wood that’s since been painted black. It seems as if it’s been here for ages – exactly the purpose it was supposed to achieve, I’m told. Windows of various shapes and sizes dominate the southern and eastern façades; some appear as though they could be original, though only due to their square shape; yet others hint at the interlocked geometries behind them. The northern and western exterior façades are composed of only glass walls. They define the light, airy extension, which spans the home’s entire length. When scanning the exterior from the southeast corner, it would hardly seem worth noticing, as typically North Hollandish materials dominate the view: red brick, clay roof tiles and, as noted, many planks of seemingly aged, reused wood. Upon looking closely, however, it becomes apparent that these façades, brick or black, bear little resemblance to those of the neighbours. On the eastern façade, the many windows dominate; on the southern façade, where the brick wall ends, a glass wall extends.

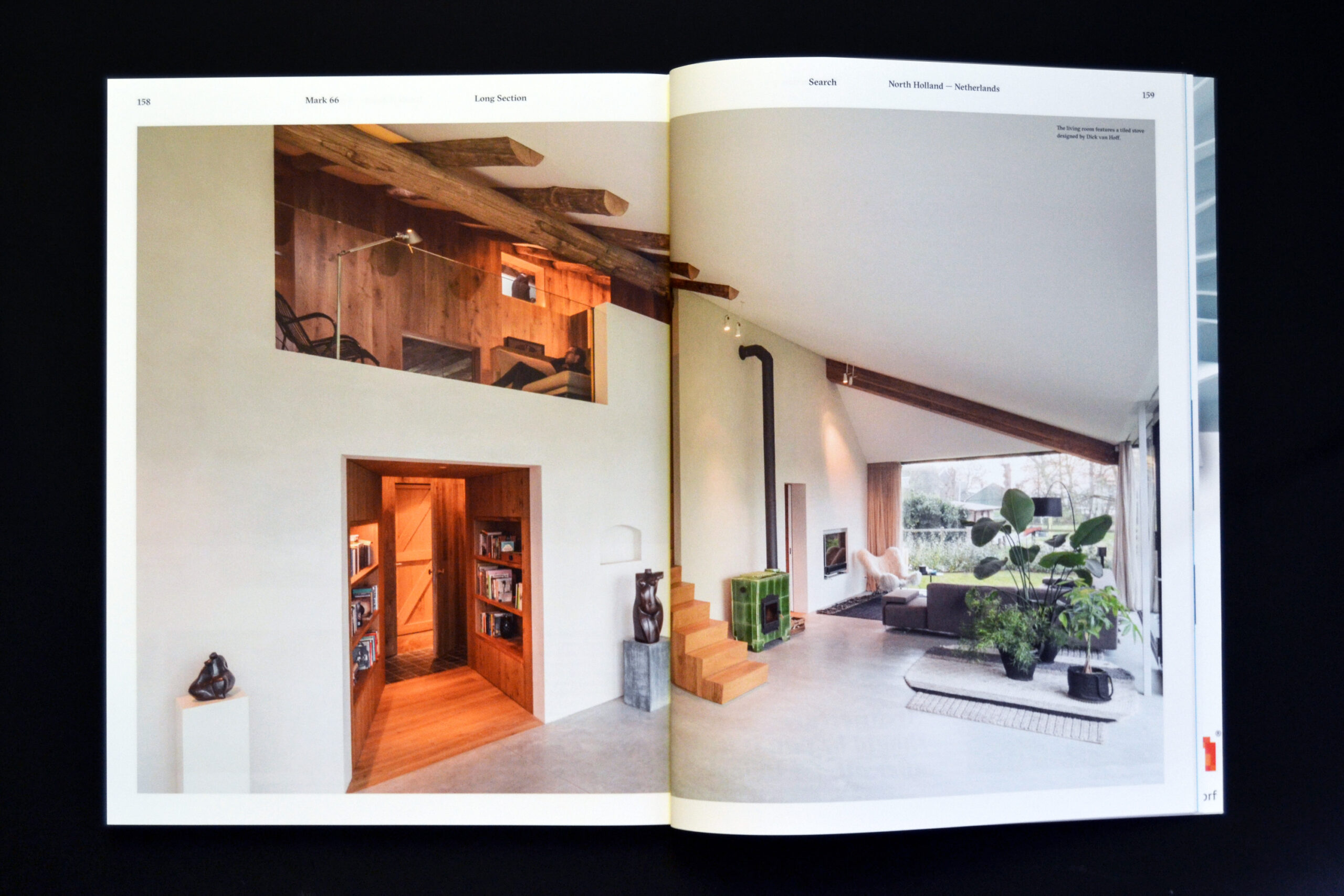

Only when entering the house, or when walking around it, does the enormous glass extension come into view. It’s roughly 6 m wide and 23 m long, and functions as a living room, dining room, and kitchen. The roof of the glass volume meets that of the original house at a slightly acute angle; in that way, the two low-sloped roofs hardly seem ‘sewn’ together, and instead appear to seamlessly merge. The original farmhouse’s typology bears the name stulp in Dutch, and a core defined the building; it is where the farm’s animals would sleep, and served as storage. Compression occurs when entering the home from its ‘traditional’ front door, and it continues when transitioning through its oak-paneled hallway, decompressing when continuing on through to the glass extension. The house’s core, which the ground floor hallway passes by, was created from the space once used as storage space for hay; it rises nearly the full height of the house, with more windows of various shapes and sizes, which offer glimpses of the surrounding interior spaces. When looking up, a spiral staircase’s encasing protrudes from one wall; it leads to a ‘second’ floor–a sort of loft-like space, atop the voided core. Hanging from the void’s ceiling is a set of gymnastic rings; hidden within it is a projection screen, to instantly transform it into an entertainment center. Play is–literally–at the center of the house.

The home’s interior recalls Adolf Loos’s labyrinthine multileveled space: his so-called Raumplan, as in Villa Müller in Prague. Numerous staircases, some with many risers and treads, others with only a few, are found throughout the house. They allow inhabitants to take many different routes to the same space within the house, by connecting them in serendipitous ways. Unexpected spaces are found off the first-floor hallway, such as a sauna. A sense of voyeurism haunts the house’s interior, as spaces interlock and interior windows offer views to spaces to which access is not always immediately evident. Yet when wandering the interior, contrasts between new and old become explicitly clear: oak wood wraps most of the former farmhouse’s surfaces; white walls define most of the newly created spaces. At the back of the house, a smaller version of it has been built, for the owners’ goats.

Search’s growing oeuvre of built work is defined by an understanding that the spaces it creates are meant for living. This philosophy means the work is rarely pretentious, or cloaked in glamour’s veil, due to cleverly staged photographs. Material luxury is subtle, understated. A sunken bedroom here, a tiny curved concrete staircase there. The house’s luxuriousness, as represented by the sauna, for instance, is of a type that needs no explanation. Recessed lighting, often within the custom millwork–such as within the cocooning, wood-paneled, ground-floor hall–heighten a sense of thoroughness; solid and respectful, yet new in form, for Search and the village. Hidden in the villa’s eastern façade, for instance, are also two new homes, for local owls. They’re expected to move in at the same time as the owners. Such humble details represent a consideration of the project, beyond only its owners’ needs. The owl houses are an apt metaphor for the firm’s design philosophy: respect the past, don’t be dictated by it, and stay open to possibilities of the unexpected. It’s within such details as the owl houses that the dialogue between client and firm can be best seen. They remind those inhabiting Search’s buildings to slow down and observe their surroundings, and encourage asking the poignant question–‘What isn’t it for?’