A Dutch city abundant in uniformity, families with children, and suburban housing, Almere is nevertheless a place where, every now and then, a gem of a private home appears among otherwise ordinary developments. Its latest jewel is a new house by Marc Koehler Architects (MKA) from nearby Amsterdam, a growing practice noted for its compact yet voluminous private housing.

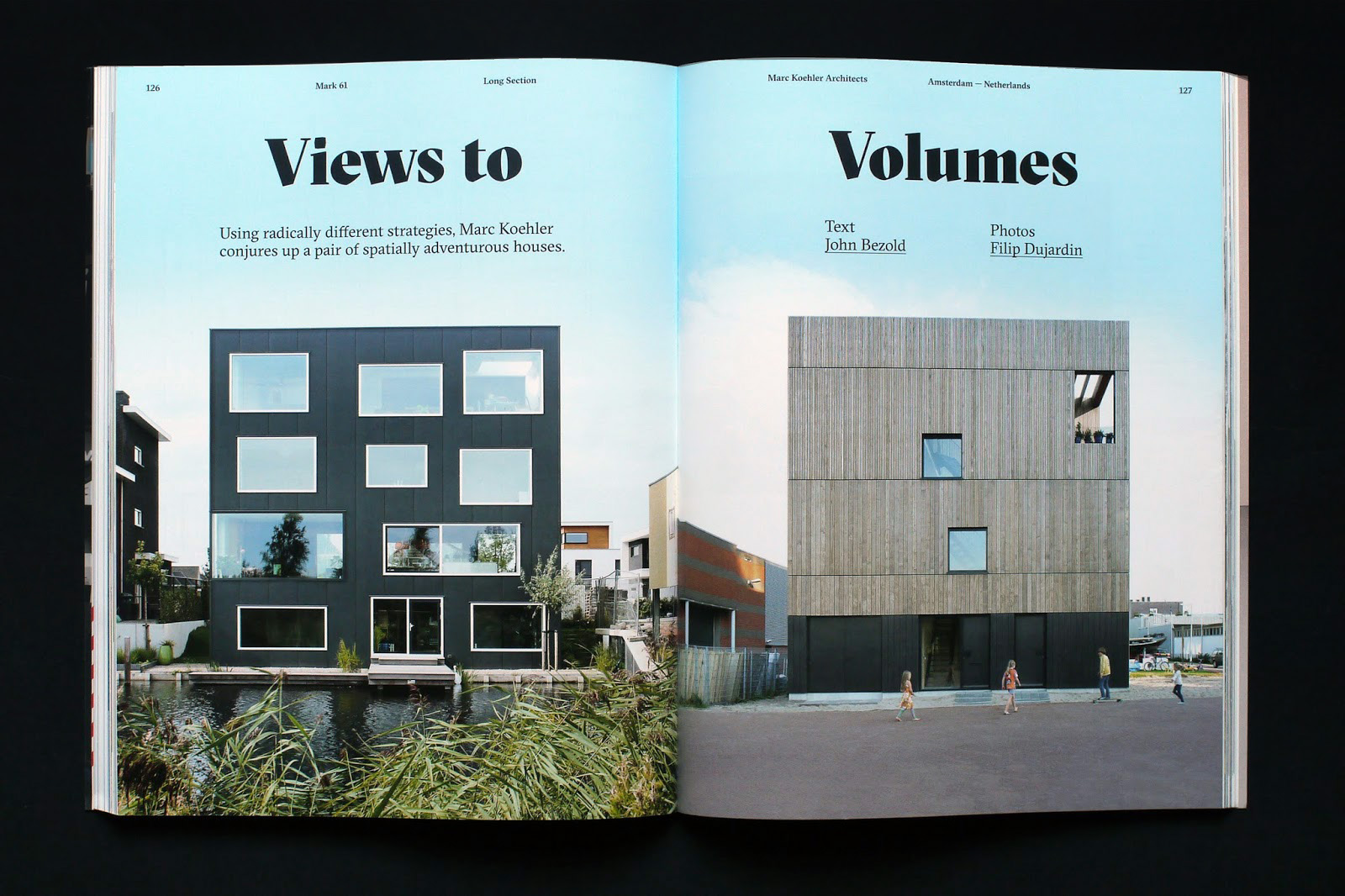

‘Almere is known for its Dutch light,’ says office founder Marc Koehler, ‘a low daylight glow that occurs because of the vast expanses of flat horizon.’ We’re on our way to see his recently completed House with 11 Views, driving along seemingly endless roads before arriving rather suddenly in a densely planned Dutch suburb. Situated on an island, the rectangular house is surrounded by 15 other single-family homes. Four storeys tall, the 240-m2 building has corrugated aluminum cladding on its main façade and, on the opposite side, panels of black siding that enable passive solar heating. Angled northwest on its narrow site, the ‘extruded box’ of a house has few openings at the front, where a lone window looks down on a large sliding door and stairs that descend from the main level to a quirky front garden.

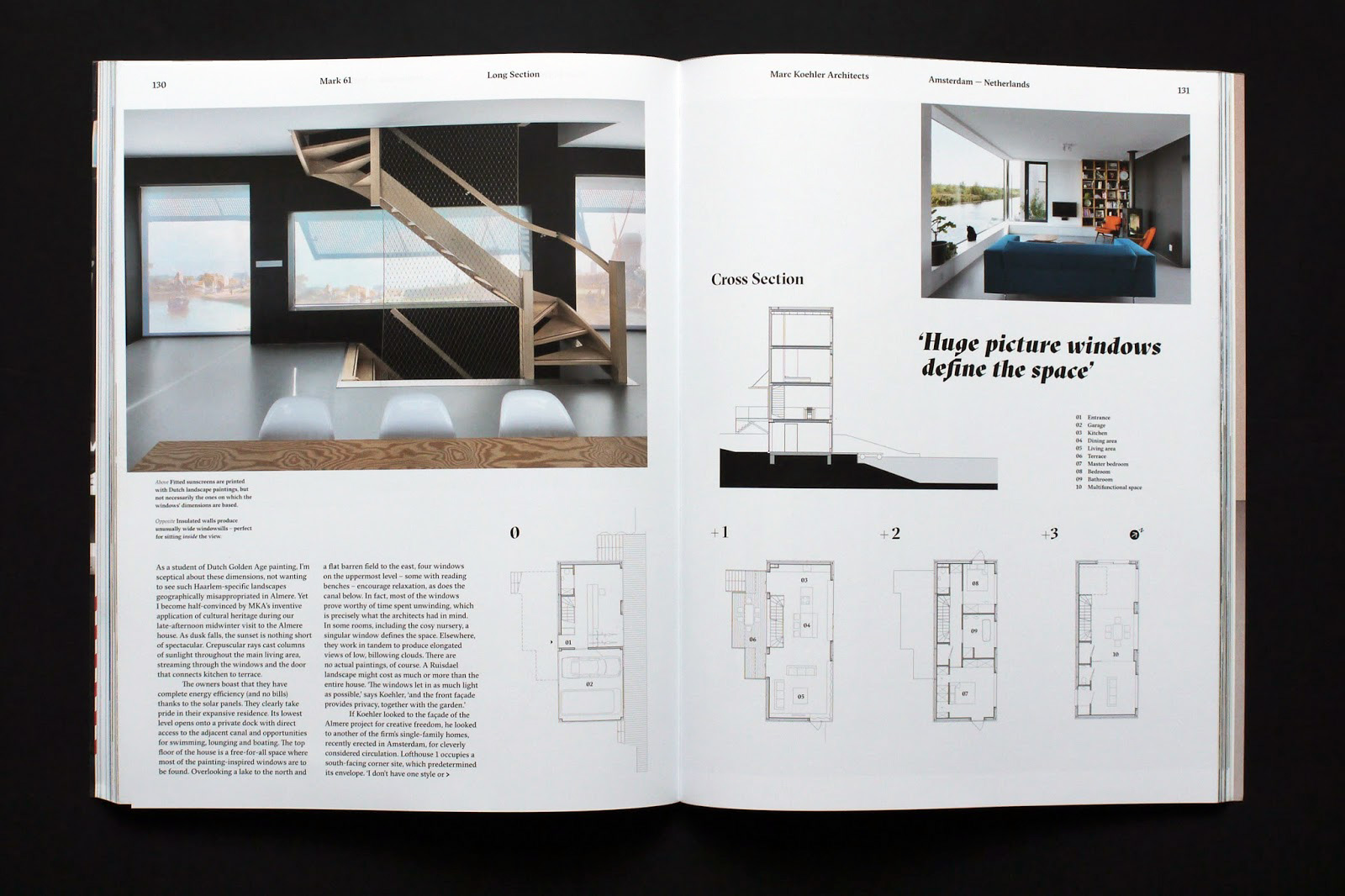

Inside, all floors are made of matte-grey polyurethane and most walls are white; an exception is the slate-grey wall next to the staircase on every floor. Windows are omnipresent. The lack of openings on the south façade is overcompensated for on the north façade, which features 11 big picture windows. Some are more playful than others, with sills lowered to floor level or built-in benches for sky gazing and afternoon reading. The dimensions of the windows, so the story goes, were derived from those of famous landscape paintings from the Dutch Golden Age, including works by Jacob van Ruisdael, Jan van Goyen, and Cornelis Vroom. The idea was that each window would be a living painting.

As a student of Dutch Golden Age painting, I’m skeptical about these dimensions, not wanting to see such Haarlem-specific landscapes geographically misappropriated in Almere. Yet I become half-convinced by MKA’s inventive application of cultural heritage during our late-afternoon midwinter visit to the Almere house. As dusk falls, the sunset is nothing short of spectacular. Crepuscular rays cast columns of sunlight throughout the main living area, streaming through the windows and the door that connects kitchen to terrace.

The owners boast that they have complete energy efficiency (and no bills) thanks to the solar panels. They clearly take pride in their expansive residence. Its lowest level opens onto a private dock with direct access to the adjacent canal and opportunities for swimming, lounging, and boating. The top floor of the house is a free-for-all space where most of the painting-inspired windows are to be found. Overlooking a lake to the north and a flat barren field to the east, four windows on the uppermost level–some with reading benches–encourage relaxation, as does the canal below. In fact, most of the windows prove worthy of time spent unwinding, which is precisely what the architects had in mind. In some rooms, including the cozy nursery, a singular window defines the space. Elsewhere, they work in tandem to produce elongated views of low, billowing clouds. There are no actual paintings, of course. A Ruisdael landscape might cost as much or more than the entire house. ‘The windows let in as much light as possible,’ says Koehler, ‘and the front façade provides privacy, together with the garden.’

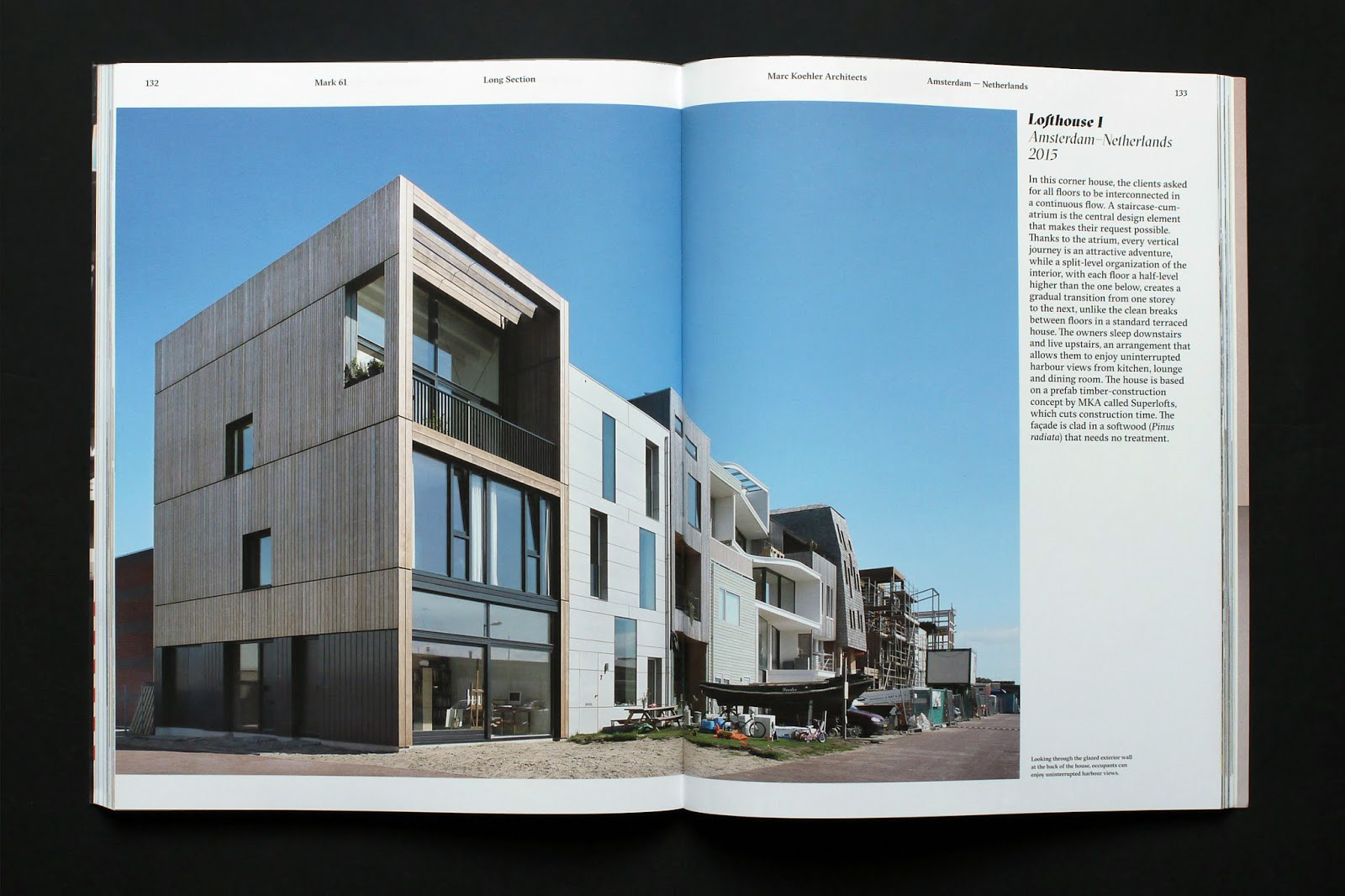

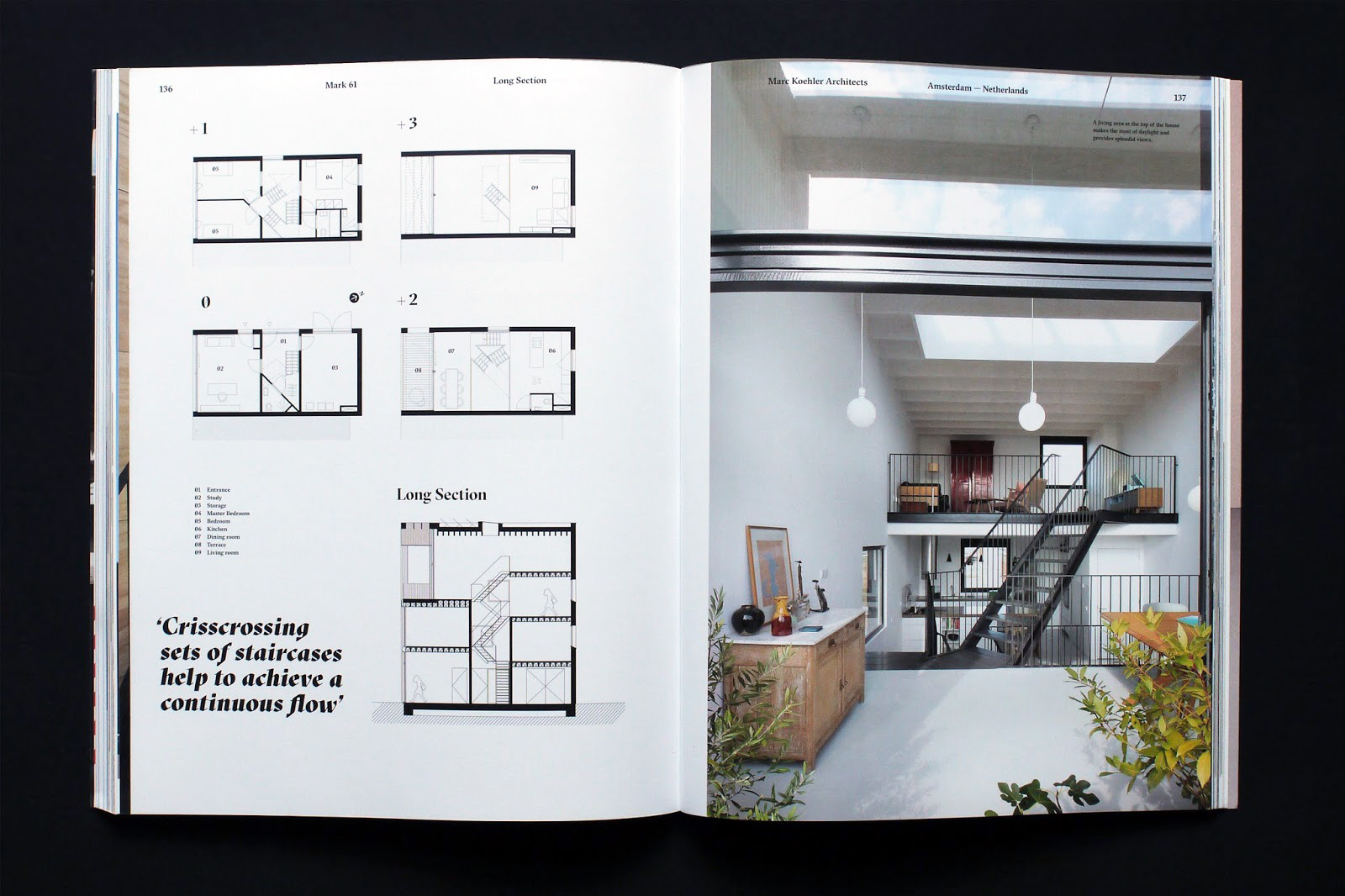

If Koehler looked to the façade of the Almere project for creative freedom, he looked to another of the firm’s single-family homes, recently erected in Amsterdam, for cleverly considered circulation. Lofthouse 1 occupies a south-facing corner site, which predetermined its envelope. ‘I don’t have one style or a singular design trademark,’ says Koehler. ‘I am still finding my way with each new project.’ Materiality, circulation, daylight: his work is not about an isolated quality but about a carefully nuanced balance of the three. His earlier Dune House and House in a House (both in Mark 54) also revealed differences in aim, materials, and, therefore, feel.

The same diversity is apparent in Lofthouse 1, a single-family timber-clad home in Amsterdam North, where a former urban harbor has been converted to a residential neighborhood, in sharp contrast to suburban Almere. Both steel-framed houses offer unobstructed views of the surroundings, yet in Amsterdam MKA opted for an atrium that is divided by crisscrossing sets of staircases and positioned living areas on higher levels. A subtle integration of site, an empathetic adherence to the client’s brief, and a willingness to place detail above material luxury are elements incorporated into Koehler’s projects. Surely in time one of them–site, form, or materiality–will emerge as the firm’s signature characteristic.

Until then, MKA’s output, especially the single-family houses in its portfolio, can be seen as whimsical experiments in volumetric exploration and division–with a focus on cleverly choreographed converging staircases, oversized picture windows seeking to resemble seventeenth-century landscape paintings, or a sly enmeshing of building and site. Koehler’s private residential projects recall the material twists and interlocking spaces that define the houses of the mid-1990s building boom in Amsterdam’s Eastern Harbour District. Perhaps they’re a more appropriate national legacy to reference than old master paintings.