As with nearly all aspects concerning the fine and applied arts, the twentieth century upended the very notion of art’s ‘acceptable’ modes of production; its formal aspects, and societal expectations; its academic traditions; and its very purpose.1 This then gave rise to new art forms and techniques. Most notably in painting, in the century’s second half—redefining art from a practice rooted in aesthetic ideals and standards, to one that’s instead a performance on the part of the artist.2 The ancient art of collage is no exception.3 Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948), and Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) all left their distinct, successive waves of patterns and ideas from their modes of creation in the medium—the word collage coined by Picasso—throughout that century.

Picasso most often took to the medium of paint to advance his own methods, using it to create illusions of three-dimensional space within a two-dimensional plane, as in his 1912 Still Life with Chair Caning. Schwitters employed, notably, words within his works as a continuation of the ideas he inherited from the Dadaists.4 Rauschenberg broke the flat surface of the work—whether its support was canvas, or otherwise—piercing the ‘fourth-wall’ to create what would come to be known as combines. That is: artworks that are meant to be affixed to a two-dimensional surface, though also intentionally neglect a painting’s traditional canvas—by creating his own from the objects that he found around him. With the most notable being his 1955 work, Bed.5 There are countless collage artists working today. Though what separates some works from the sea of collages now being created, are the intellectual patterns of thought on the part of artists. Most notably, those artists who seek not to recreate the aesthetic idealisms of the nineteenth-century academies, nor those of its predecessor: the Ancien Régime.

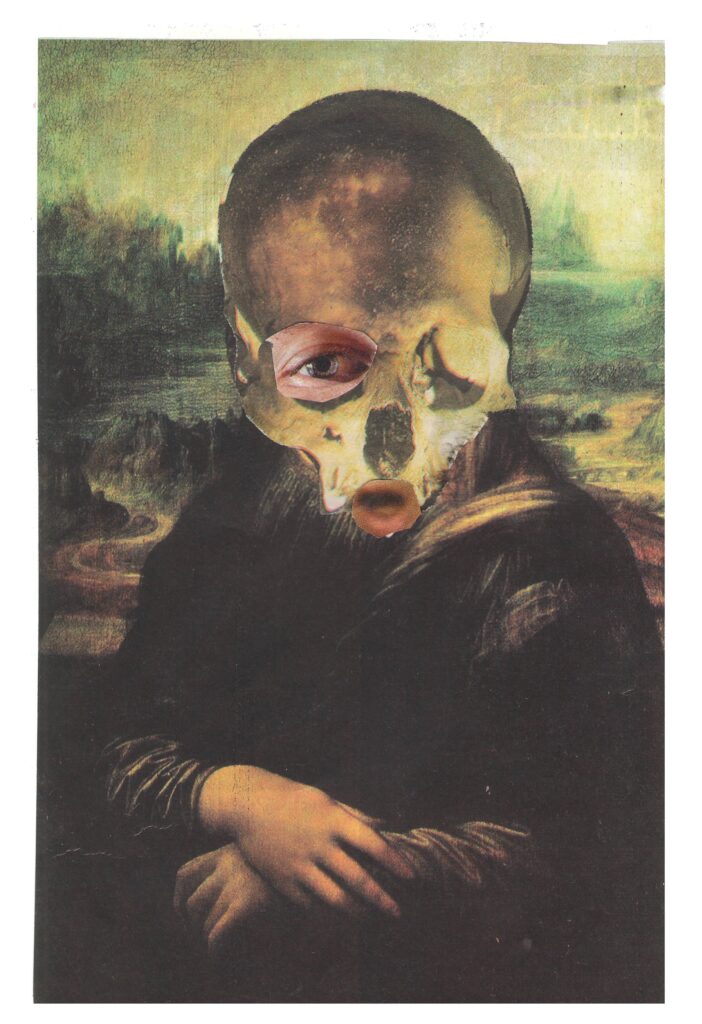

Roya Khodadad (1996) is a Tabriz, Iran-based collage artist, who in her own way, has continued innovating the traditions of collage developed during the mid-twentieth century—though with digital post-production. She is not alone in this, and her overall aim is not solely beauty. This last part lends to her oeuvre, a cohesiveness; though not because of a computer, even as it plays a role in her process. But there’s also no reluctance toward using it. Ostentatiousness isn’t present in her work, via, for instance, an insistence on abstract constraints, such as using a certain number of colors, or a fixed amount of components per collage. Creativity reigns supreme in these mesmerizing worlds. Her source materials command presence, as does her recontextualization of historical figures; drawing on a desire to bring awareness to society’s omniscient undercurrents—such as poverty, mass consumerism, and the need to relax restrictive modes of thinking around the positions the historical figures in her work, inhabit in history. She and I spoke about her background, her aim to express concern for the good of society, as a whole, and how she uses her art to bring awareness to such issues.

What attracted you to art, and what is your background—beyond collage?

For the past two years, I have been studying for my undergraduate degree in carpet design. I started my professional life in this field, being largely self-taught, and I have always been interested in collages. Since I was a child, my passion for art has always been present. I used to spend my spare time painting and crafting, and as I grew older, this interest became more pronounced. One day, I decided to choose art as my field of study. It should be noted that in addition to art (mostly painting, drawing, and photography) I’m very interested in dramatic literature.

Who is your favorite artist and what aspects of their work do you admire?

This is a very hard question to answer because I’ve learned so many different types of visual language from each artist I’m interested in. But most of the time when posed with this question, I always answer Lucien Freud (1922-2011). I admire his style and the way he’s created a layered language using paint.

Your publicly available work is all in college. Why do you create within this medium, and what is it about it that’s inspired you to create them yourself?

It was, actually, my mother who always used to argue with me about creating art. Specifically, because of the number of old magazines, and older papers, and other unusable books that I have always kept in my library. This is mostly because old magazines took up quite a lot of space in my library, in her eyes, with no actual purpose. She wanted to throw them away. This was the spark to fuel my passion to enter the fascinating world of collages myself, and perhaps, give a second chance to all the ‘old’ papers that were going to be thrown into the garbage! I think this is the most appropriate and beautiful technique for making collages; using found, older imagery.

How do you choose what to use from your library, in terms of the subjects that do find their way into your collages? From reading books; internet inspiration?

Magazines are the best material for my work. I’m very excited right now when I think about magazines because they’re endless. They’re full of pictures, all with different themes and historical periods. There really isn’t better material for making collages.

Could you talk about and describe, how you create your work, in terms of the process behind each one?

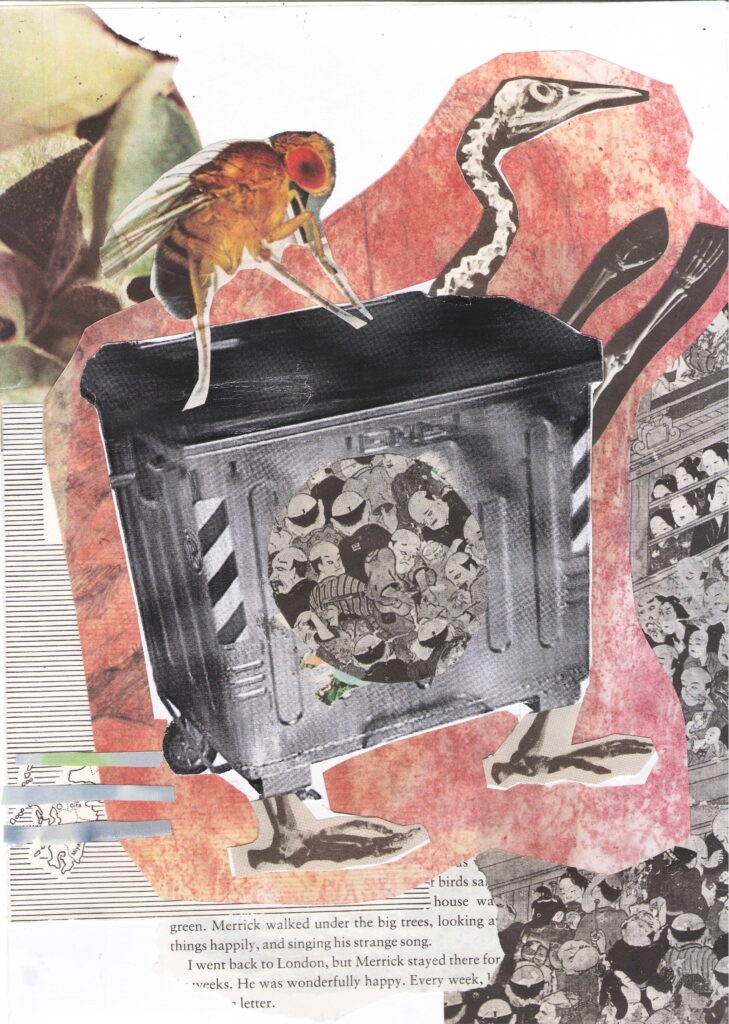

I can say that in two ways, this happens and takes shape. First, so that I have no idea what my new work is: I go to my pictures, I take a few examples from them, and then I select a group to take away from that. The second method is to consider the idea and the subject, and then start. Poverty, for example, is one of the issues that has always been a concern for me—and images that are in relation to this issue. The improvised events that take place during my process, are always appealing to me.

Much of your work is centered on the themes of society; how people are perceived on a societal level. What are the dominant themes in your work?

I think it has become clear that one of my concerns and perhaps the most important one, is the problems of the society for people—and this is not just about my own country. In general, I believe that each and every one of us is responsible for society, as a whole, and each other. I try to use this idea in my work with the knowledge I have gained from the topic of composition. Even the horizontal or vertical cadre helps narrate the works. Apart from collecting various types of old papers, I also collect clothes that are no longer used, to help stop the cycle of consumption and support sustainable fashion. Because the environment and the planet need our attention now, more than ever.

Your collages are layered in ways that usually have one main object of central focus. But they are also complete worlds. How do you approach composition?

I don’t limit my focus to one composition type. I try to use it in my work with the knowledge I’ve gained from the topic of composition. Even the horizontal or vertical cadre helps to narrate each work. So, I don’t limit my focus to one type, and instead, I always try to use different compositions to express myself. Further, my principles of composition are combined from my learned experience, of photography and drawing.

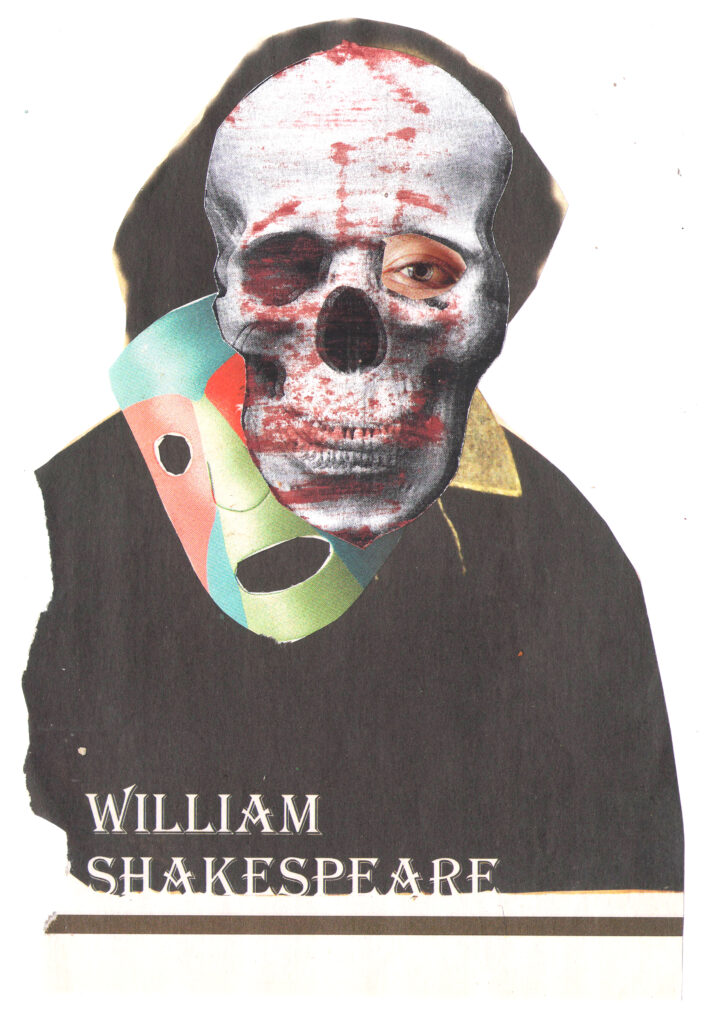

Concerning your series named ‘Face Off’… Why have you focused on historical figures: Abraham Lincoln, Shakespeare, and Van Gogh?

As I explained, my materials are mostly sourced from magazines. So many older magazines are full of famous people’s cold, serious faces. I collect those faces, and it is interesting for me to make a collection that could be fun, to present a different version of them.

‘Lost in the Papers’ is an evocative series name—and the title of your largest collection to date. What do you mean by papers? Old papers in your library?

When I first started creating collages, I would begin and realize that I was often, quite literally, lost between many different piles of paper around me. I was actually, losing myself in the process of being lost in papers, in the best possible sense. I am entirely absorbed in my work when creating collages. So I chose the title ‘Lost in Papers’.

Since you predominately use the medium of NFTs to distribute your work out into the world—what do you do with the original collages; the actual paper?

I always keep the original works with me. Sometimes I’ll also take pictures of them, mostly just to share my process and to communicate more with my audience online.

White space in your work seems to be equally as important as the composition. How does the absence of collage elements, contribute to your overall aesthetic?

White space, for me, plays a very important role in my work. I try to use white space intentionally to frame compositions. Even if I need to eliminate it altogether and not keep it entirely, then I’ll often make sure that in the background, some of the artefacts and objects that I’ve made central features of my work, are framed in cream colors. Another point to note is that most of my work does not have a dictated frame. It is all organic and I do not digitally crop.

Lastly, can you talk about your process of digital post-production? Could you explain your approach to how this affects the final version of your collages? They all have a very soft, inviting tone to them. And beyond that—do you also paint or draw on them? How do you create the depth present in your work?

I transform the physical collages to a digital format by scanning them for their best possible resolution—rather than photographing them. I do use Photoshop but only to adjust light, contrast, and color. This makes the output of the work similar to its physical version. I never want to lose their uniqueness with too much digital editing.

The reason my work has a soft tone to it is that I try to choose images with close color range. Other than that, I don’t use any digital filters, at all, in terms of matching colors from one part of the work to another.

I have always liked to use different media in my work—and have always enjoyed that. For this reason, in some works, I do use markers, oil paints, and acrylic paints. Oil and acrylic paint, because it helps to create a lot of coverage on the work, and gives it a volume. I also use colored markers, to give the work certain transparency. Every new medium I introduce has its own effect; and in fact, I sometimes use them randomly.

- See for instance: Natalie Adamson, Painting, Politics, and the Struggle for the École de Paris, 1944-1964 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009).↑

- Delia Ciuha and Raphael Bonnier, Action Painting: Jackson Pollock (Olfildern, Hate Cantz: 2008).↑

- For a historical overview of collage see: Eddie Wolfram, History of Collage: An Anthology of Collage, Assemblage, and Event Structures (London: Studio Vista, 1975). For a more recent survey of the topic see: Patrick Elliott, Freya Gowrley, and Yuval Etgar, Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2019).↑

- Stefan Themerson, Kurt Schwitters on a Time-Chart (Oude Tonge: Huis Clos, 1998), 11. ‘It seems that those works of art, by many artists, in which the fact of their being an aesthetic achievement overpowered the fact of their being an event, survived the time corrosion better. Most of Kurt Schwitters’ work, and especially that produced during 1923-1928, belongs there. Shall I say that a collage by Schwitters is appreciated now not because it was hip, but because it has become a square, as much square as Mona Lisa, both with and without her mustache. Or am I wrong?’↑

- Herbert Read, A Concise History of American Painting (New York City: Thames & Hudson), 286-302.↑