A favorite quote of mine, borrowed from Disney’s instant classic Ratatouille, reads as so; ‘The world is often unkind to new talent, new creations. The new needs friends’–which is certainly more than true. Designers, architects, artists; they’re all shaping our future–but will society accept their changes? And what exactly is being created that’s changing the way we think about our world?

Neri Oxman can be described as an architect. That is, if you were to strictly base her professional title on her educational background. But what she practices is a profession that doesn’t fall into any of today’s conventional categories. So much so that Oxman has deemed herself ‘professionally homeless’, even refusing to use the term ‘architecture’ to describe her work. The terms theorist, structural engineer, biologist, and the self-coined ‘material ecologist’ would all be a better fit; as well as describe her work with much more precision. Oxman’s work, and the theories propelling it, has pulled back a curtain that is often left closed. She’s shining a very focused beam of light on a subject that is rarely seen in the architectural world–the creation of something new.

‘If we can represent the form of the human body through the distribution of load, temperature, humidity, sounds, and smell; why are we still designing decorated sheds!?’ Oxman wonders. A question that has quite the strong point; why are we? Have architects become obsolete? It’s this question that forms the basis of Oxman’s research and exploration into the world of materials.

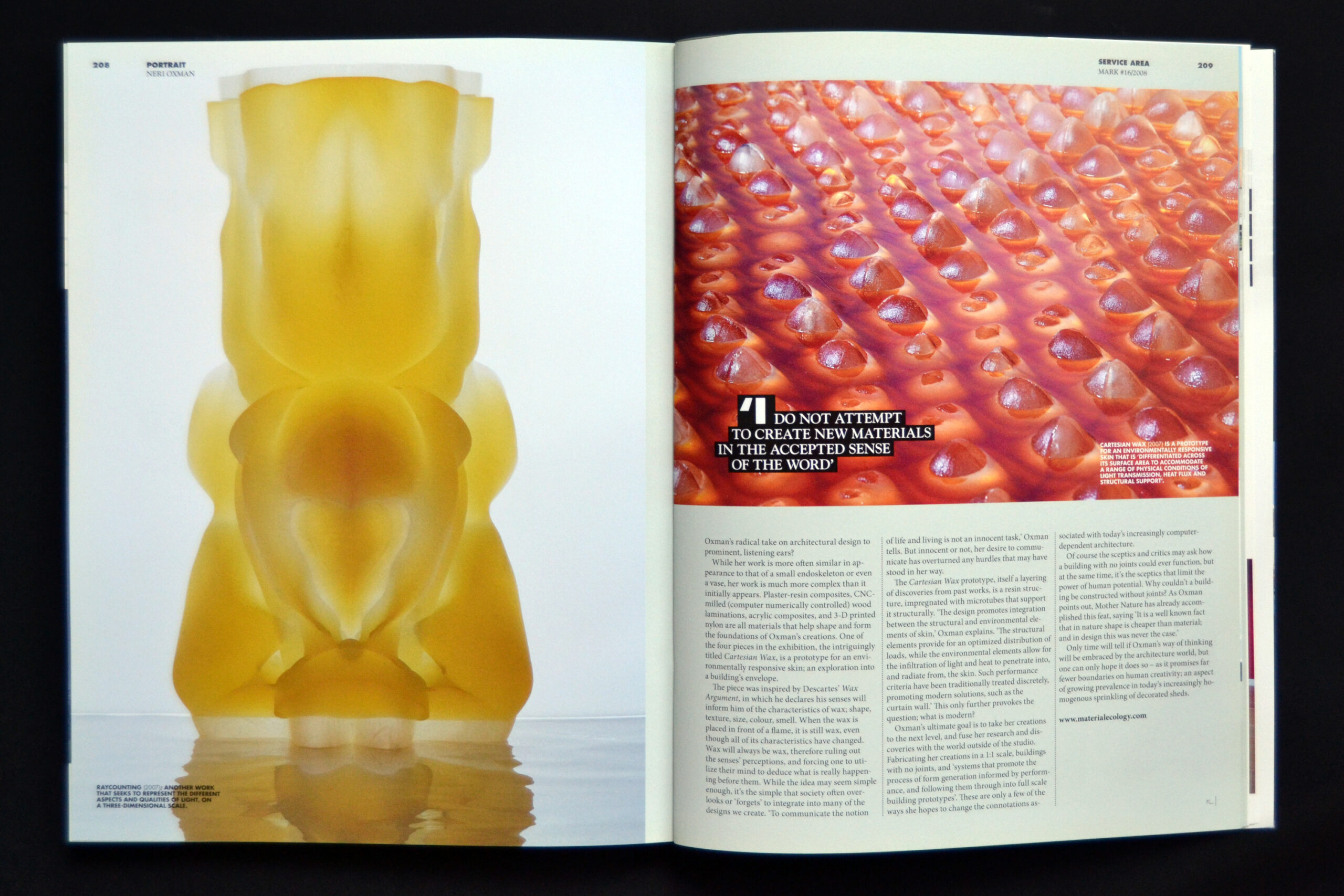

‘I do not attempt to create new materials in the accepted sense of the word,’ she says. ‘I research towards a better understanding of material behavior which applies to the architectural scale.’ This undertaking has fuelled Oxman to explore the realm of materials, not through the idea of the final product, but through process–a practice long forgotten or neglected in today’s bottom-line driven world.

Paralleling and expanding on the ideas of those who pioneered environmental and site-specific architecture–most notably Alvar Aalto–Oxman begins by ‘outlining the constraints from which to draw inspiration. These include the specificities of environmental conditions at a given site, the typical conditions to be achieved, as well as and their effect on the environment through heat, temperature, humidity, and load.’

And while she looks to the future for the implementation of her process, designs, and hypothetical structures, she doesn’t look towards modern architecture as a means of inspiration. Rather, she draws on ‘the primal knowledge of material practice, such as craft and primitive structures, attempting to consciously reject ideas about form and typology which lie outside of performance and behaviour’–a philosophy she feels has long been absent.

Since Oxman’s architectural innovations reject the formalities of today’s ‘modern architecture of repetition’, she views most of her contemporaries as merely, ‘designers who have defined their individuality through formalistic attributes, which may be regarded as style’.

But as ‘architecture’ continues to be created by today’s studios, whose founders are now known on a one-name basis (you know who they are), and whose architecture is now given common nicknames (the Bird’s Nest and Water Cube for example), one can’t help but wonder; is this really architecture?

At one end, one could argue that architecture is nothing more than a structure created through constraints; constraints placed on the site, on the user, and by architects themselves. Out of all these constraints emerges a beautiful purpose-built structure, brought to life by a ‘one name’ architect who has clearly bettered the world through their contribution and role as ‘architect as artist’. But on the opposite end of the spectrum lies a belief that these beautiful buildings are nothing more than very expensive sculptures–with toilets. Have we come to regard these glorified sculptures, toilets included, as the future of architecture?

Oxman hopes to reverse the ideas and goals currently emphasized in modern design and architecture, and once again show the world how, ‘built environments may be conceived as living things, rather than immaculate conceptions’. A passionate view of hers that only strengthens her desire to create, and show the world, something new.

It would appear that immaculate conceptions seem to be all the rage today, with one of the most famous being Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, California. To counter this battle, Oxman has turned to nature and the human body, once again calling on the ideas of those before her. This time she’s going back as far as the first century BC, to the philosophical viewpoints of Vitruvius, and his favorite subject–the human body.

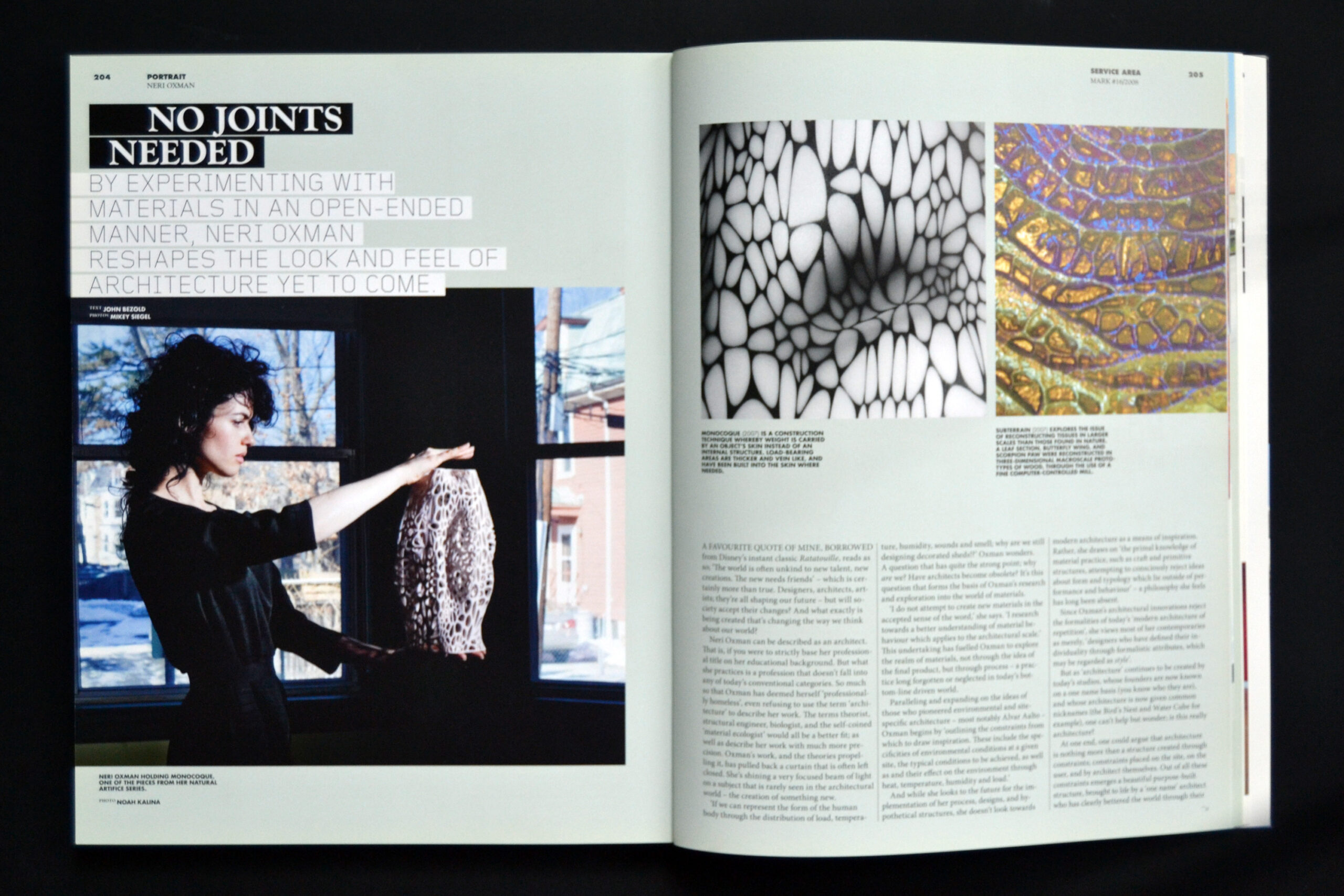

Going back to the roots of architecture is sure to be re-welcomed into society, especially with the recent advent of sustainable design, currently gaining in prominence. But Oxman has taken her thoughts and explorations one step further than those of the past ever dreamt of, and it’s this extra step that’s making her work stand out among others’; the idea of material as skin.

‘The idea of skin indeed stands out as the subject of much of my work,’ Oxman explains. ‘This is mainly due to skin’s remarkable ability to act as both a filter and a barrier, which is what we expect a building’s envelope to do throughout its lifetime. Skin demonstrates the incorporation of multiple performance types, as it is both load sustaining and environmentally responsive. In its capacity to negotiate comfort with strain, it is a complex structure, operating across many scales of behavior and effect.’

The ‘modern’ architecture movement has been celebrated for the standardization and repetition in its design, most noticeably its façades. But most architectural movements are essentially an adverse reaction to their predecessors, and as the movements of the twenty-first-century show, no one movement sticks around for too long. Is Oxman laying the foundations for an emergence of a new architectural style? If so, the outcome might be unlike anything the world has ever laid eyes on.

One could even say the current push towards sustainable design is nothing more than a return to environmental awareness that has been lost over the years, mainly due to the ever-increasing role of computers. Instead of hailing the computer for its role in creating immaculate conceptions, should we have instead been using these advances in technology in more useful ways? The answer is yes, and Oxman proves this by showing the world how technology can do more than create undulating façades and screens of titanium.

Introducing the world to a new way of thinking is often a difficult task, generating much speculation and skepticism. A coveted media outlet, such as the MoMA in New York, is one of the most distinguished channels for communicating new ideas to the world. But positions inside such well-known ‘idea incubators’ are hard to secure, and are limited to a select group each year. But earlier this year the MoMA itself handpicked Oxman for inclusion in one of its exhibitions–commissioning her to design a four-piece series she’s named Natural Artifice. ‘Design and the Elastic Mind’, as the general exhibition was titled, features ‘new initiatives at the intellectual and productive interface between science, art, and design’–and what better media outlet to introduce Oxman’s radical take on architectural design to prominent, listening ears?

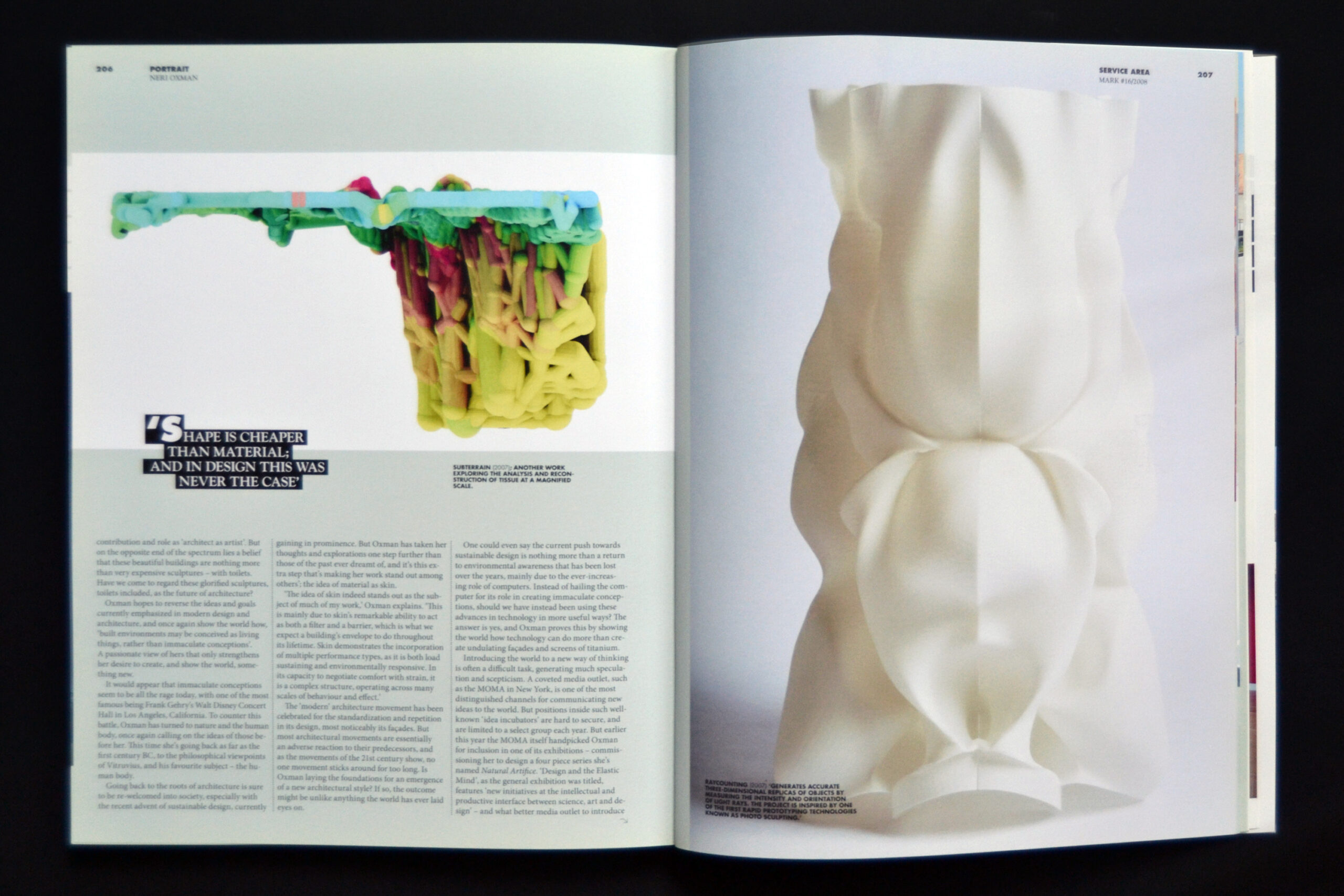

While her work is more often similar in appearance to that of a small endoskeleton or even a vase, her work is much more complex than it initially appears. Plaster-resin composites, CNCmilled (computer numerically controlled) wood laminations, acrylic composites, and 3-D printed nylon are all materials that help shape and form the foundations of Oxman’s creations. One of the four pieces in the exhibition, the intriguingly titled Cartesian Wax, is a prototype for an environmentally responsive skin; an exploration into a building’s envelope.

The piece was inspired by Descartes’ Wax Argument, in which he declares his senses will inform him of the characteristics of wax; shape, texture, size, color, smell. When the wax is placed in front of a flame, it is still wax, even though all of its characteristics have changed. Wax will always be wax, therefore ruling out the senses’ perceptions, and forcing one to utilize their mind to deduce what is really happening before them. While the idea may seem simple enough, it’s the simple that society often overlooks or ‘forgets’ to integrate into many of the designs we create. ‘To communicate the notion of life and living is not an innocent task,’ Oxman tells. But innocent or not, her desire to communicate has overturned any hurdles that may have stood in her way.

The Cartesian Wax prototype, itself a layering of discoveries from past works, is a resin structure, impregnated with microtubes that support it structurally. ‘The design promotes integration between the structural and environmental elements of skin,’ Oxman explains. ‘The structural elements provide for an optimized distribution of loads, while the environmental elements allow for the infiltration of light and heat to penetrate into, and radiate from, the skin. Such performance criteria have been traditionally treated discretely, promoting modern solutions, such as the curtain wall.’ This only further provokes the question; what is modern?

Oxman’s ultimate goal is to take her creations to the next level, and fuse her research and discoveries with the world outside of the studio. Fabricating her creations in a 1:1 scale, buildings with no joints, and ‘systems that promote the process of form generation informed by performance, and following them through into full-scale building prototypes’. These are only a few of the ways she hopes to change the connotations associated with today’s increasingly computer-dependent architecture.

Of course the skeptics and critics may ask how a building with no joints could ever function, but at the same time, it’s the skeptics that limit the power of human potential. Why couldn’t a building be constructed without joints? As Oxman points out, Mother Nature has already accomplished this feat, saying ‘It is a well-known fact that in nature shape is cheaper than material; and in design, this was never the case.’

Only time will tell if Oxman’s way of thinking will be embraced by the architecture world, but one can only hope it does so–as it promises far fewer boundaries on human creativity; an aspect of growing prevalence in today’s increasingly homogenous sprinkling of decorated sheds.